Towards a whole-enterprise architecture standard – 4: Content

Blog: Tom Graves / Tetradian

For a viable enterprise architecture [EA], now and into the future, we need frameworks, methods and tools that can support the EA discipline’s needs.

This is Part 4 of a six-part series on proposals towards an enterprise-architecture framework and standard for whole-of-enterprise architecture:

- Introduction

- Core concepts

- Core method

- Content-frameworks and add-in methods

- Practices and toolsets

- Training and education

This part explores how various reference-frameworks, checklists and add-in methods could be used in conjunction with the core-method described in the previous part of this series, in alignment with the core concepts described in Part 2 of the series.

Rationale

The conventional content-first approach to ‘enterprise’-architecture is to package up a set of content-specifications – checklists, reference-architectures and suchlike – along with the architecture-development method (if any), and present it as a framework to guide development for the respective domain. For example, the current version of NAF (NATO Architecture Framework) lists some 46 distinct sets of views and/or artefacts that supposedly need to be developed for a complete architecture.

And yes, that works well enough for architecture-development in a single domain, or across a tightly-constrained set of domains.

The catch is that it won’t work for whole-enterprise architecture. As per the ‘Core concepts’ described earlier in this series, whole enterprise architecture must be able to cover any and every aspect of the enterprise – including any subset, superset and/or intersecting-set of or with the respective enterprise.

Which means that any framework for whole-enterprise architecture must be able to support any required content-frame.

Otherwise known as everything.

Many of the existing content-first frameworks are impracticably huge already. But this would be a book of almost literally infinite size.

And just to make it even more fun, the necessarily fractal, emergent, multi-layered nature of the architecture-development method that we need for whole-enterprise architecture, as per Part 3 of this series, also means that we often won’t – and can’t – know in advance what content-frames we’ll need to use. Which means, in book-format or a conventional website, we’d have no meaningful way to index that impossibly-huge document anyway, to find the content-frames and methods that we need, when we need them.

We’re going to need to tackle this in a different way.

Although there are no doubt many options that could work well, one option that I’ve explored for quite a while now has the added virtue of simplicity. It’s this: map out the metacontext for whole-enterprise architecture via a small number of metaframes.

This would provide a set of context-identifiers with which to ‘tag’ more context-specific frames and methods.

Such ‘tagging’ would enable us to identify the zones of the metacontext to which each frame or method would validly apply.

It would also enable us to check for overlaps and gaps in framework or method coverage for architecture-work in a given real-world context.

All of which is technically precise, but probably won’t make much sense at first. At this point most people would probably need some explanation at least of all that ‘meta-’ jargon…

The metacontext is a context of contexts – a kind of abstract overview of the entire possible set of contexts that might be covered in whole-enterprise architecture. In effect, ‘metacontext’ is a kind of one-word summary for ”the everything’ as everything’.

A metaframe is an abstract frame that describes or encapsulates common-factors or other elements that occur in some way in many or most other frames, and that we can use to categorise those other frames. In effect, a metaframe is a frame for frames, in much the same way that a metamodel is a model for describing models, or metadata is data about data.

In short, what it means is that if we have some way to create a useful set of tags, we can use those tags to help identify, within the total ‘the everything’, the respective coverage provided by each available frame or method in our existing toolbox.

This gives us a means to identify our tools’ overlaps and gaps in coverage for a given type of context – much like overlays of cellphone network-coverage maps can show us overlaps and gaps in overall coverage. And it also gives us a means to compare tools and their coverages on roughly equal terms, and get those differing tools to ‘play nicely’ with each other, too. Which is really useful – especially at a whole-enterprise level.

So how do we do this, in practice?

To me at least, it looks like we could get a very good start on this with just four sets of tags:

- asset-dimensions supported

- decision/skill-levels supported

- applicable levels of abstraction

- architecture-focus (maturity-model)

(One further set of tags – “architecture-phases in which to use this” – would link each content-item more tightly to the architecture-method, though these would be more as guidelines rather than identifiers)

Four sets of tags no doubt doesn’t sound much – yet there are so many crosslinks that it actually multiplies out to a much richer set of descriptors than it might at first seem.

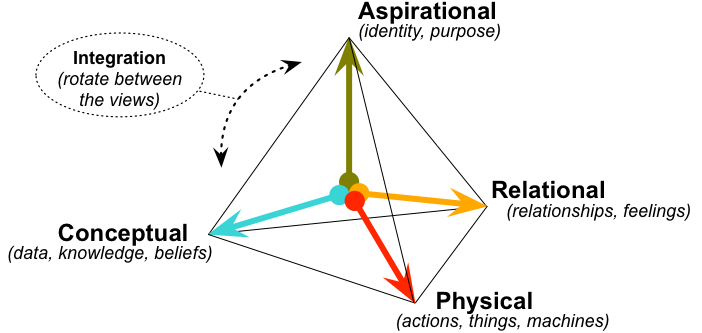

To illustrate this, let’s start with the tetradian for the asset-dimensions:

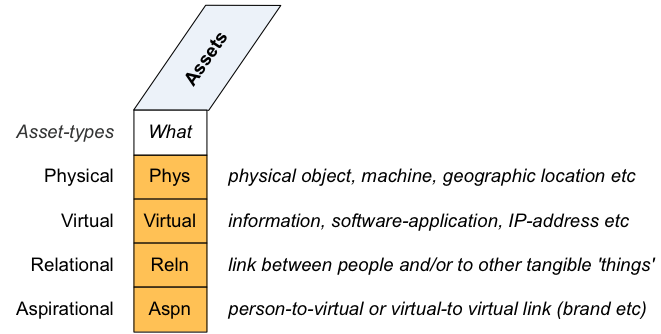

Which we can expand out into a graphic-checklist:

In the terms used in service-oriented modelling with Enterprise Canvas, the asset-dimensions apply to asset, function, location, agent of capability, action-upon of capability, and event of a service, and also to a product as asset. In more detail:

- physical: physical object, machine, location etc;

as asset, is tangible, independent (it exists in its own right), exchangeable (I can pass the thing itself to you), alienable (if I give it to you, I no longer have it) - virtual: information, software-application, IP-address etc;

as asset, is non-tangible, semi-independent (exists in its own right, but requires association with something physical to give it accessible form), semi-exchangeable (I can pass a clone or imperfect-copy of the thing to you), non-alienable (if I give it to you, I still have it) - relational: link between people, or people and other tangible ‘things’;

as asset, is semi-tangible (each end of the link is tangible), dependent (it exists betweenits nodes, and may be dropped from either end), non-exchangeable (if I have it, I cannot give it to you – though I can create conditions under which you could create your own equivalent copy), inherently non-alienable (there is nothing that can be given to others) - aspirational (‘meaning’): person-to-virtual link (such as memory of grandparent, or association with/to an enterprise or a brand), or virtual-to-virtual (such as links between brands in a brand-architecture, or relationship between model and metamodel in a schema);

as asset, is semi-tangible at best (one end of the link may be tangible, but at least one node will be virtual), dependent (it exists between its nodes), non-exchangeable (as for relational-asset), inherently non-alienable (as for relational-asset)

And although most real-world entities represent a combination of two or more of those dimensions, there are distinct differences at the asset-dimension level in how we create, read, update and delete each type of asset – which adds to the reasons why we need to identify, in this way, what frameworks and methods would act on or describe.

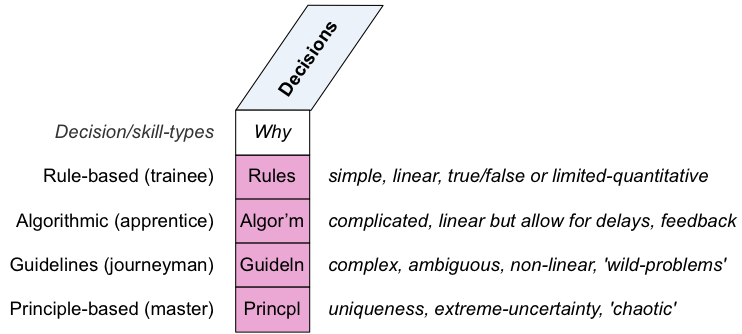

Somewhat related to the asset-dimensions, but also distinct in their own right, are the decision/skill-level dimensions:

In service-modelling with Enterprise Canvas, the decision/skills dimensions apply to skill-level of capability, and decision/reason for use within a service:

- rule-based (Trainee): simple, linear, true/false or limited-quantitative rules, applicable in real-time contexts; typically the only type of decision-making available to a physical machine, a low-level software-element or a trainee-level real-person

- algorithm-based (Apprentice): potentially-complicated but linear true/false or quantitive algorithms, potentially including any number of factors, delays, feedback-loops etc, but often not directly applicable in real-time contexts; typically not available to physical machines, but available to a higher-level software-element and an apprentice-level real-person

- pattern/guideline-based (Journeyman): methods for complex, ambiguous, non-linear, qualitative, ‘wild-problem‘ contexts, addressing experiment and uncertainty, though often not directly applicable in real-time contexts; typically not available to physical machines or to conventional true/false-type software-based systems, but available to ‘fuzzy-logic’ software-systems or a journeyman-level real-person

- principles-based (Master): methods for uniqueness, extreme-uncertainty and/or ‘chaotic’-type contexts, especially at real-time; rarely available to physical-machines or software-based systems, but typically available to master-level real-person

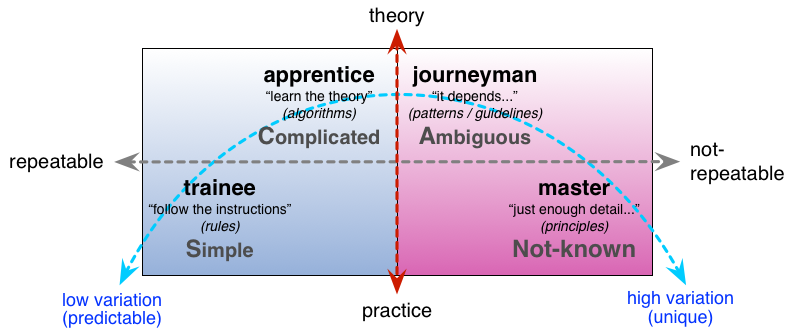

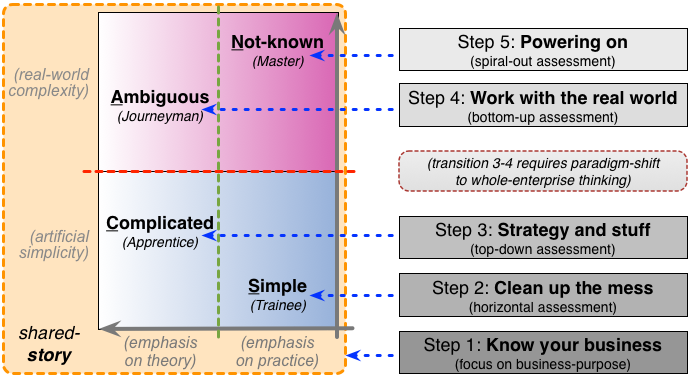

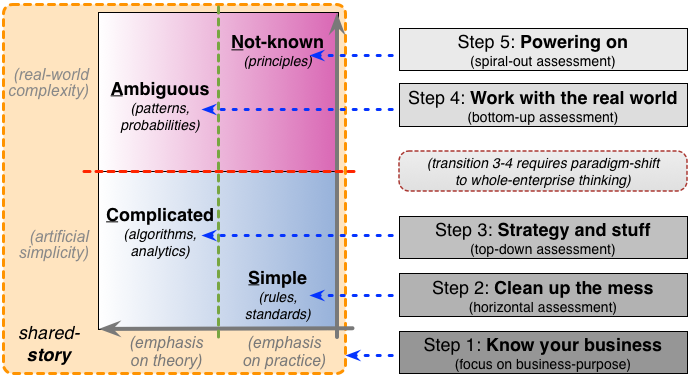

Again, tagging of frames and methods with these dimensions helps to clarify what skill-levels the respective frames or methods require or describe, and what levels of complexity they address. The latter also provides a useful crossmap to the SCAN framework on sensemaking, decision-making and complexity:

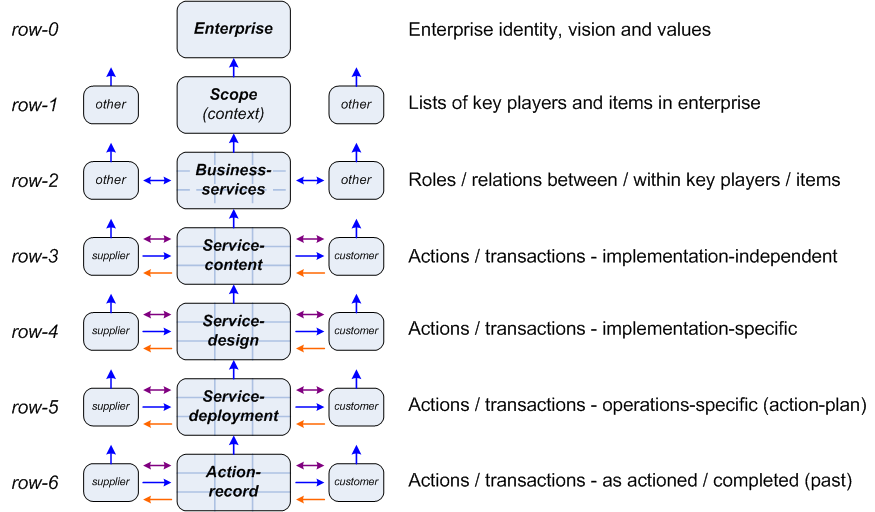

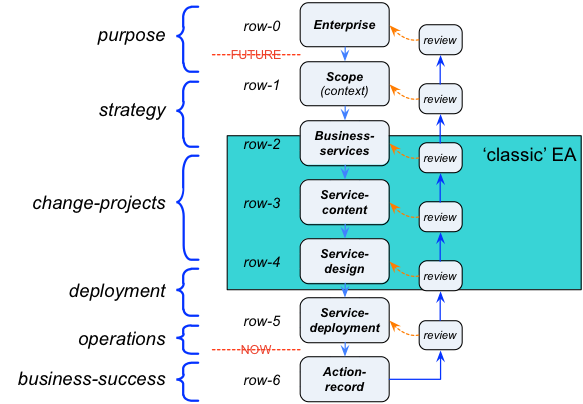

The next frame, that perhaps provides the most directly-useful set of tags for this purpose, is the layers-of-abstraction model that we saw back in Part 2 of this series. The crucial point, for here, is that these layers each represent or require different levels of detail, different types and structures of architecture-content:

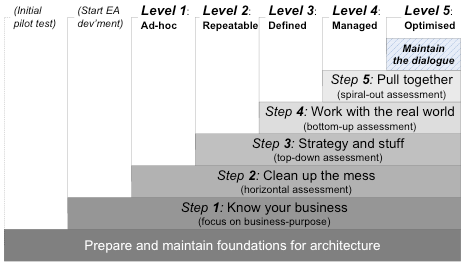

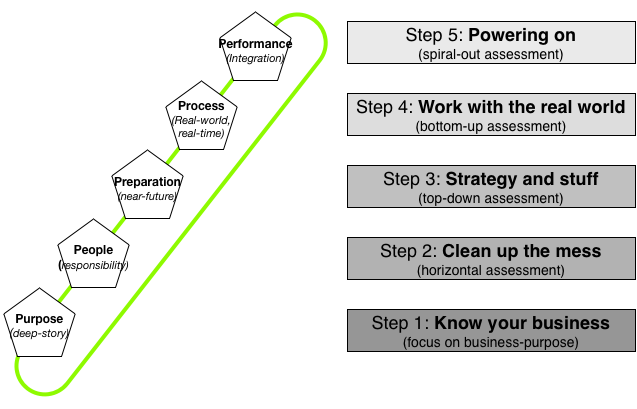

Finally, we can use the ‘layers’ – more accurately, development-steps and architecture-focus areas – of the maturity-model that we saw in Part 3 of this series, and that we’ll return to again in Part 5:

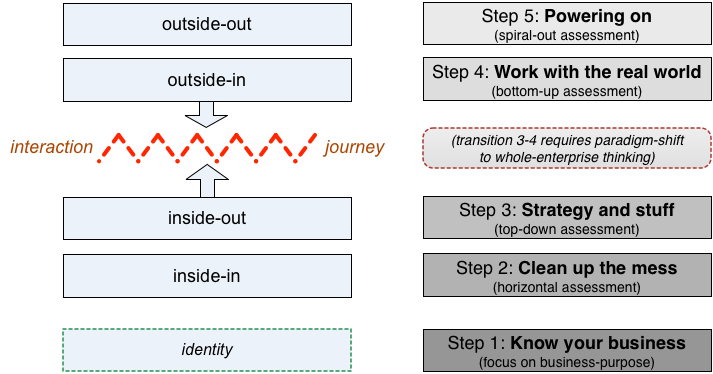

In turn, there’s a direct crossmap between the maturity-model and the perspectives-model (inside-in, inside-out, outside-in, outside-out) that we also saw in Part 2:

Which also, via SCAN, would crossmap to the typical minimum skill-level at each maturity-step:

And thence to the typical decision-tactics we would expect to see in use at that maturity-step, and in architecture-development for that maturity-step:

Which, of course, also crosslinks back to the decision/skills-dimensions describe earlier above.

In other words, there’s a lot that we can do with just those four sets of tags – and they’re quite tightly interlocked with each other, too.

By the way, there’s also a crossmap between the maturity-model and the Five Elements model used as the basis for the framework’s metamethod. It’s not quite as exact as the other crossmaps above, but still close enough to be useful. (There’s further explanation of this in the post ‘Anthropomorphise your applications?‘.)

Anyway, to bring this back the key point here, how would all of this work in practice?

Let’s take a real example. Imagine that we’re developing an enterprise-architecture for a factory-floor – a full modern assembly-line with a mix of robots and human activity, a lot of sensors, a lot of mechanical forming and assembly, and some complex materials-activities such as welding, painting, heat-treatment. Someone’s suggested that we could use the TOGAF/Archimate pairing to guide the architecture for this purpose. Using the tagging-system above, we could identify what parts of the scope that that framework would cover, if used as a ‘plug-in’ to the architecture-development method described in Part 3.

First, in terms of the asset-dimensions, even the most recent versions of TOGAF and Archimate are pretty solidly IT-centric – which implies some quite severe constraints on the types of assets and activities that framework could cover:

- physical: IT-hardware only (e.g. sensors and servers but no actual machines; data-flows but not physical material-flows)

- virtual: main focus, but computer-based only (e.g. not physical kanban-board)

- relational: human activities only in context of IT (e.g. as ‘user’ for input or output, but not machine-operation or machine-maintenance)

- aspirational: optional, via ‘Motivation’ plug-in

Next, in terms of the decision/skills-level dimensions, the IT-centrism in effect constrains TOGAF and Archimate to the limits of capability of the respective IT-systems – which in most cases would be the first two levels only, namely rule-based and algorithm-based.

In common with most mainstream ‘EA’-frameworks, the the current TOGAF/Archimate pairing cover only the mid-range of the layers-of-abstraction model:

For example, if we were to use the TOGAF-9 ADM (Architecture Development Method) as a ‘plug-in’ for our whole-enterprise architecture metamethod, the TOGAF-ADM phases would map to the layers-of-abstraction model roughly as follows:

- row-0 (whole-of-enterprise): no coverage

- row-1 (enterprise-scope): probably no coverage

- row-2 (business-services): Phases A/B (partial)

- row-3 (service-context): Phases B/C/D

- row-4 (service-design): Phases E/F/G

- row-5 (deployment): probably no coverage

- row-6 (action-records): possibly some coverage indirectly via Phase C and Phase H

Finally, for the maturity-model, the mapping is more on different TOGAF versions:

- Step 1 (‘What business are we in?’): minimal coverage

- Step 2 (‘Clean up the mess/Tidy the house’): TOGAF v8 – IT-related data, apps and IT-infrastructure only

- Step 3 (‘From strategy to execution’): TOGAF v9 – IT-related business-strategy and services

- Step 4 (‘This is the real-world talking’): minimal coverage

- Step 5 (‘Pull together/Bring on the pain’): minimal to no coverage

Which, overall, tells us the following things:

- we can almost certainly use TOGAF/Archimate for some of our factory-floor architecture (because it will cover at least some of our context-scope)

- we cannot reliably attempt to use TOGAF/Archimate for all of our factory-floor architecture (because there are significant gaps in whole-enterprise coverage for our context)

- we’ll need to use other plug-in frames and methods to cover the parts that TOGAF/Archimate cannot reach

In other words, using this approach, we can still maintain the value of our previous investment in TOGAF/Archimate – but we explicitly identify and acknowledge their limitations. In particular, we drop the expectation (or delusion?) that they can and must cover every part of a real whole-enterprise scope. Instead, we build and maintain a broader set of plug-ins that, between them, can cover the full scope of any context within which we need to work.

(Getting all of these frames and methods to ‘play nicely’ with each other within toolsets is a different problem, but we’ll leave that until Part 5.)

Again, all I’ve described above are a suggested or default set of sets of tags that we could use for this purpose. There would almost certainly be many other tag-sets that would prove useful, particularly for more specialist needs. The key focus here is not the tags themselves, but the overall principle of using tags to guide how plug-in frames and methods can be used within and in conjunction with the whole-enterprise architecture metamethod.

Application

From the above, we can derive suggested text for the ‘Content-frameworks and add-in methods’ section of a possible future standard for whole-enterprise architecture. Some of the graphics above might also be included along with the text.

– Scope of content-frameworks and context-specific methods [‘content’]: The required overall scope for content for whole-enterprise architecture will be every aspect of every possible enterprise. It is not feasible to attempt to cover this by a single, predefined, all-encompassing package of content.

– Relationship between content and metamethod: The metamethod described for whole-enterprise architecture is intentionally minimalist and context-agnostic. Since context-specific content would constrain the metamethod to that respective context, the metamehod embeds no prodefined content other than its own usage-guidelines. On its own, however, the metamethod is too abstract to be usable for much more than a quick completeness-check: it need to be linked to context-specific content to make it directly usable and applicable for any specific context.

– Linking content to metamethod: Content (context-specific frames and methods) may be attached to and detached from the metamethod, according to the needs and scope of the respective context. In other words, all content-items are considered to be ‘plug-ins’ to the metamethod.

(When the metamethod is implemented within an EA-toolset, the respective toolset must directly support this linking and de-linking of content frames – more on that in Part 5 of this series.)

– Applicability of content within the metamethod: A simple mechanism such as a system of tagging should used to identify the applicable scope of recommended-usage and validity for each plug-in frame or method. If tagging is used for this purpose, the tag-sets themselves will be attached as plug-ins to the metamethod, within and as the metametamodel for its implied metaframework. The commonality of tagging (or equivalent) will enable assessment of overlaps and gaps in coverage between content-items selected for usage in a given context.

– Guidance on usage of content: Because the effective scope for whole-enterprise-architecture – and hence for the metaframework, metamethod and overall required context-specific content – is potentially infinite, no specific usage-guidance is or can be provided within the metaframework, other than for the basic usage of the metamethod itself. To resolve this, it is expected that communities of practice will develop around particular types of usages and/or contexts (e.g. brand-architecture, experience-architecture, service-architecture, ‘digital transformation’ etc). The combination of shared usage of the metamethod itself, and the use of tagging or equivalent to identify scope of content-items, will enable commonality, crosslinking and shared-practices across the entire whole-enterprise scope, and at all layers-of-abstraction from strategy to execution and back again.

Overall, in less-technical form:

- By intent, there are no predefined reference-frameworks, context-specific methods or other ‘content-items’ predefined for and/or hard-wired to the architecture method (the ‘metamethod’) outlined in Part 3.

- Instead, every content-item is a ‘plug-in’.

- Treating context-specific content-items as plug-ins in effect enables infinite scope for the framework and method.

- We use a simple mechanism such as tagging to identify the types of scope and context for which each plug-in content-item would validly apply. Doing so also makes it relatively simple to identify overalsp and gaps in coverage for a given context.

- The tag-sets used to identify scope and suchlike are themselves plug-ins. This means that the overall set of tags available for use within the framework is itself extensible according to EA-community needs – again, potentially to infinity. In practice, we’ll probably need some kind of community-based repository to list and maintain governance of shared or standard tags, beyond the default sets of tags described in the ‘Rationale’ section above.

The above provides a quick overview of how we can handle context-specific reference-frameworks, methods and so on within a metaframework that has potentially-infinite scope. Again, it’s nowhere near complete-enough for a formal ‘standards-proposal, but it should be sufficient to act as a strawman for further discussion, exploration and critique.

But how do we use this, in real-world practice? What kind of toolset-support do we need for that practice? That’s what we’ll move on to look at next, in the next part of this series. In the meantime, though, any questions or comments so far?

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.