Thought Experiment: How Einstein Solved Difficult Problems

Blog: FS - Smart decisions

Thought experiments are a classic tool used by many great thinkers. They enable us to explore impossible situations and predict their implications and outcomes. Mastering thought experiments can help you confront difficult questions and anticipate (and prevent) problems.

***

The purpose of a thought experiment is to encourage speculation, logical thinking and to change paradigms. Thought experiments push us outside our comfort zone by forcing us to confront questions we cannot answer with ease. They demonstrate gaps in our knowledge and help us recognize the limits of what can be known.

“All truly wise thoughts have been thought already thousands of times; but to make them truly ours, we must think them over again honestly, until they take root in our personal experience.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Famous thought experiments

Thought experiments have a rich and complex history, stretching back to the ancient Greeks and Romans.

An early example of a thought experiment is Zeno’s narrative of Achilles and the tortoise, dating to around 430 BC. Zeno’s thought experiments aimed to deduce first principles through the elimination of untrue concepts.

In one instance, the Greek philosopher used it to ‘prove’ motion is an illusion. Known as the In one instance, the Greek philosopher used it to ‘prove’ motion is an illusion. Known as the dichotomy paradox, it involves Achilles racing a tortoise. Out of generosity, Achilles gives the tortoise a 100m head start. Once Achilles begins running, he soon catches up on the head start. However, by that point, the tortoise has moved another 10m. By the time he catches up again, the tortoise will have moved further. Zeno claimed Achilles could never win the race as the distance between the pair would constantly increase.

Descartes conducted a thought experiment, doubting the existence of everything he could until there was nothing left he could doubt. Descartes could doubt everything except for the fact that he could doubt. His process left us with the philosophical thought experiment of ‘a brain in a vat’.

In the 17th century, Galileo used thought experiments to affirm his theories. One example is his thought experiment involving two balls (one heavy, one light) which are dropped from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Prior philosophers had theorized the heavy ball would land first. Galileo claimed this was untrue, as mass does not influence acceleration.

According to Galileo’s early biography (written in 1654), he dropped two objects from the Leaning Tower of Pisa to disprove the gravitational mass relation hypothesis. Both landed at the same time, ushering in a new understanding of gravity. It is unknown if Galileo performed the experiment itself, so it is regarded as a thought experiment, not a physical one.

In 1814, Pierre Laplace explored determinism through ‘Laplace’s demon.’ This is a theoretical ‘demon’ which has an acute awareness of the location and movement of every single particle in existence. Would Laplace’s demon know the future? If the answer is yes, the universe must be linear and deterministic. If no, the universe is nonlinear and free will exists.

In 1897, the German term ‘Gedankenexperiment’ passed into English and a cohesive picture of how thought experiments are used worldwide began to form.

Albert Einstein used thought experiments for some of his most important discoveries. The most famous of his thought experiments was on a beam of light, which was made into a brilliant children’s book. What would happen if you could catch up to a beam of light as it moved he asked himself? The answers led him down a different path toward time, which led to the special theory of relativity.

Natural tendencies

In On Thought Experiments, 19th-century Philosopher and physicist Ernst Mach writes that In On Thought Experiments, 19th-century Philosopher and physicist Ernst Mach writes that curiosity is an inherent human quality. Babies test the world around them and learn the principle of cause and effect. With time, our exploration of the world becomes more and more in depth. We reach a point where we can no longer experiment through our hands alone. At that point, we move into the realm of thought experiments.

Thought experiments are a structured manifestation of our natural curiosity about the world.

Mach writes:

Our own ideas are more easily and readily at our disposal than physical facts. We experiment with thought, so as to say, at little expense. It shouldn’t surprise us that, oftentime, the thought experiment precedes the physical experiment and prepares the way for it… A thought experiment is also a necessary precondition for a physical experiment. Every inventor and every experimenter must have in his mind the detailed order before he actualizes it.

Mach compares thought experiments to the plans and images we form in our minds before Mach compares thought experiments to the plans and images we form in our minds before commencing an endeavor. We all do this — rehearsing a conversation before having it, planning a piece of work before starting it, figuring out every detail of a meal before cooking it. Mach views this as an integral part of our ability to engage in complex tasks and to innovate creatively.

According to Mach, the results of some thought experiments can be so certain that it is unnecessary to physically perform it. Regardless of the accuracy of the result, the desired purpose has been achieved.

“It can be seen that the basic method of the thought experiment is just like that of a physical experiment, namely, the method of variation. By varying the circumstances (continuously, if possible) the range of validity of an idea (expectation) related to these circumstances is increased.”

Ernst Mach

Thought experiments in philosophy

Thoughts experiments have been an integral part of philosophy since ancient times. This is in part due to philosophical hypotheses often being subjective and impossible to prove through empirical evidence.

Philosophers use thought experiments to convey theories in an accessible manner. With the aim of illustrating a particular concept (such as free will or mortality), philosophers explore imagined scenarios. The goal is not to uncover a ‘correct’ answer, but to spark new ideas.

An early example of a philosophical thought experiment is Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, which centers around a dialogue between Socrates and Glaucon (Plato’s brother.)

A group of people are born and live within a dark cave. Having spent their entire lives seeing nothing but shadows on the wall, they lack a conception of the world outside. Knowing nothing different, they do not even wish to leave the cave. At some point, they are led outside and see a world consisting of much more than shadows.

Plato used this thought experiment to illustrate the incomplete view of reality most of us have. Only by learning philosophy, Plato claimed, can we see more than shadows.

Upon leaving the cave, the people realize the outside world is far more interesting and fulfilling. If a solitary person left, they would want others to do the same. However, if they return to the cave, their old life will seem unsatisfactory. This discomfort would become misplaced, leading them to resent the outside world. Plato used this to convey his (almost compulsively) deep appreciation for the power of educating ourselves. To take up the mantle of your own education and begin seeking to understand the world is the first step on the way out of the cave.

Moving from caves to insects, here’s a thought experiment from 20th-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Imagine a world where each person has a beetle in a box. In this world, the only time anyone can see a beetle is when they look in their own box. As a consequence, the conception of a beetle each individual has is based on their own. It could be that everyone has something different, or that the boxes are empty, or even that the contents are amorphous.

Wittgenstein uses the ‘Beetle in a Box’ thought experiment to convey his work on the subjective nature of pain. We can each only know what pain is to us, and we cannot feel another person’s agony. If people in the hypothetical world were to have a discussion on the topic of beetles, each would only be able to share their individual perspective. The conversation would have little purpose because each person can only convey what they see as a beetle. In the same way, it is useless for us to describe our pain using analogies (‘it feels like a red hot poker is stabbing me in the back’) or scales (‘the pain is 7/10.’)

Thought experiments in science

Although empirical evidence is usually necessary for science, thought experiments may be used to develop a hypothesis or to prepare for experimentation. Some hypotheses cannot be tested (e.g, string theory) – at least, not given our current capabilities.Theoretical scientists may turn to thought experiments to develop a provisional answer, often informed by Occam’s razor.

In a paper entitled Thought Experimentation of Presocratic Philosophy, Nicholas Rescher writes:

In natural science, thought experiments are common. Think, for example, of Einstein’s pondering the question of what the world would look like if one were to travel along a ray of light. Think too of physicists’ assumption of a frictionlessly rolling body or the economists’ assumption of a perfectly efficient market in the interests of establishing the laws of descent or the principles of exchange, respectively.

In a paper entitled Thought Experiments in Scientific Reasoning, Andrew D. Irvine explains that thought experiments are a key part of science. They are in the same realm as physical experiments. Thought experiments require all assumptions to be supported by empirical evidence. The context must be believable, and it must provide useful answers to complex questions. A thought experiment must have the potential to be falsified.

Irvine writes:

Just as a physical experiment often has repercussions for its background theory in terms of confirmation, falsification or the like, so too will a thought experiment. Of course, the parallel is not exact; thought experiments…no do not include actual interventions within the physical environment.

In Do All Rational Folks Think As We Do? Barbara D. Massey writes:

Often critique of thought experiments demands the fleshing out or concretizing of descriptions so that what would happen in a given situation becomes less a matter of guesswork or pontification. In thought experiments we tend to elaborate descriptions with the latest scientific models in mind…The thought experiment seems to be a close relative of the scientist’s laboratory experiment with the vital difference that observations may be made from perspectives which are in reality impossible, for example, from the perspective of moving at the speed of light…The thought experiment seems to discover facts about how things work within the laboratory of the mind.

“We live not only in a world of thoughts, but also in a world of things. Words without experience are meaningless.”

Vladimir Nabokov

Biologists use thought experiments, often of the counterfactual variety. In particular, evolutionary biologists question why organisms exist as they do today. For example, why are sheep not green? As surreal as the question is, it is a valid one. A green sheep would be better camouflaged from predators. Another thought experiment involves asking: why don’t organisms (aside from certain bacteria) have wheels? Again, the question is surreal but is still a serious one. We know from our vehicles that wheels are more efficient for moving at speed than legs, so why do they not naturally exist beyond the microscopic level?

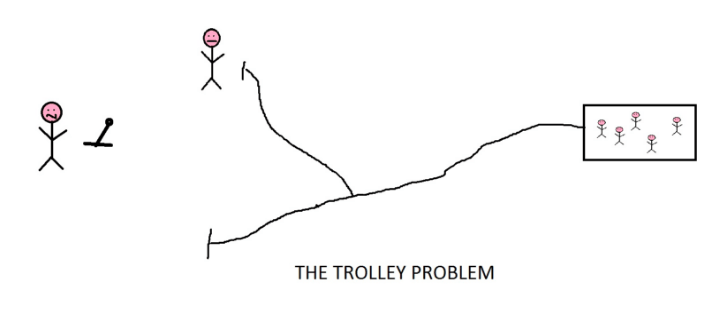

Psychology and Ethics — The Trolley Problem

Picture the scene. You are a lone passerby in a street where a tram is running along a track. The driver has lost control of it. If the tram continues along its current path, the five passengers will die in the ensuing crash. You notice a switch which would allow the tram to move to a different track, where a man is standing. The collision would kill him but would save the five passengers. Do you press the switch?

The Trolley Problem was first suggested by philosopher Phillipa Foot, and further considered extensively by philosopher Judith Jarvis Thompson. Psychologists and ethicists have also discussed the trolley problem at length, often using it in research. It raises many questions, such as:

- Is a casual observer required to intervene?

- Is there a measurable value to human life? I.e. is one life less valuable than five?

- How would the situation differ if the observer were required to actively push a man onto the tracks rather than pressing the switch?

- What if the man being pushed were a ‘villain’? Or a loved one of the observer? How would this change the ethical implications?

- Can an observer make this choice without the consent of the people involved?

Research has shown most people are far more willing to press a switch than to push someone onto the tracks. This changes if the man is a ‘villain’- people are then far more willing to push him. Likewise, they are reluctant if the person being pushed is a loved one.

The trolley problem is theoretical, but it does have real world implications. As we move towards autonomous vehicles, there may be real life instances of similar situations. Vehicles may be required to make utilitarian choices – such as swerving into a ditch and killing the driver to avoid a group of children.

The Infinite Monkey Theorem and Mathematics

“Ford!” he said, “there’s an infinite number of monkeys outside who want to talk to us about this script for Hamlet they’ve worked out.”

Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

In Fooled By Randomness, Nassim Taleb writes:

If one puts an infinite number of monkeys in front of (strongly built) typewriters, and lets them clap away, there is a certainty that one of them will come out with an exact version of the ‘Iliad.’ Upon examination, this may be less interesting a concept than it appears at first: Such probability is ridiculously low. But let us carry the reasoning one step beyond. Now that we have found that hero among monkeys, would any reader invest his life’s savings on a bet that the monkey would write the ‘Odyssey’ next?

The infinite monkey theorem is intended to illustrate the idea that any issue can be solved through enough random input, in the manner a drunk person arriving home will eventually manage to fit their key in the lock even if they do it without much finesse. It also represents the nature of probability and the idea that any scenario is workable, given enough time and resources.

To learn more about thought experiments, and other mental models, check out our book series, The Great Mental Models.

The post Thought Experiment: How Einstein Solved Difficult Problems appeared first on Farnam Street.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.