You Can’t Always Get What You Want

Blog: Tyner Blain

The shift from talking about what we want to build to talking about the problems we want to solve is easy to understand, but can be difficult to do well. We have to make decisions about which problems we will solve first. We have to make decisions about how grand of a solution we want to create. Talking about value is how we do both.

The Size of the Problem

When a leadership team is setting direction for their company, they start with a vision and their first thoughts about strategy. I love Richard Rumelt’s definition of strategy, defined in Good Strategy Bad Strategy.

The kernel of a strategy contains three elements: a diagnosis, a guiding policy, and coherent action.

Diagnosis is about problem identification. And coherent action is the approach we’re going to take to address it. All told, this is what Rumelt calls “a cohesive response to an important challenge.”

There’s a step of sense making where leaders will simultaneously explore their understanding of the key challenge and a coherent action – identifying the actionable problems which must be addressed. This is high-level problem decomposition. If the challenge is around customer retention, the problems could be around service quality, product fit, pricing, or responses to competition. “Losing too many customers” is too abstract to throw at a product team in a large organization. But improving service quality or neutralizing a competitor’s advantage – those are good meaty problems a team can sink their teeth into.

Capacity Constraints Force Choices

As my friend Rich Mironov has said at least a hundred time, we have no shortage of good ideas. We have to choose which problems we will solve and which we won’t. If we’re smart about it, we will decide which problem to solve first and which to solve second, so we begin reaping the rewards of our first effort while we are working on our second.

Leadership teams want to shape their strategies in pursuit of Rumelt’s “cohesive response”, and should do it in partnership with their product managers. A natural first step towards shortening the list of problems is to eliminate all of the problems which are too small. We also eliminate the ones which are misaligned, too uncertain, or beyond our capability to solve. For now, let’s focus just on size.

Your instinct for where to start is solid – start with the largest problem. Use a good problem statement template and make sure you are quantifying in economic terms, so you can compare the value of solving two very different problems. In a discussion with a client this past week I asked “how do you decide which is more important – increasing customer adoption or reducing customer billing errors?” When you don’t use economics to create a frame for comparison your choices are still driven by intuition.

The Problem of… We have revenue leakage of $10M per year because of billing errors

Affects Whom… Customers, customer support, product line general manager

The Impact of Which is… $2M per year in EBITDA at a 20% gross margin

The Benefits of a Solution are… $2M per year in increased EBITDA through reclaiming $10M in revenue

This looks great. It absolutely defines the size of the problem.

But you can’t always get what you want.

The Size of the Solution

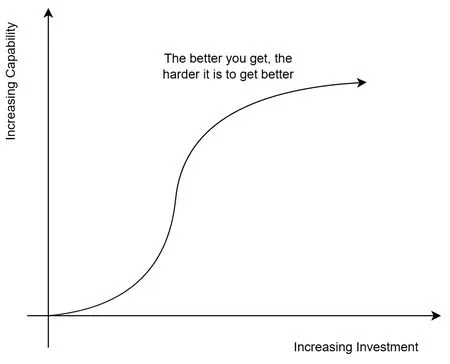

If we had magic wands, we could just choose the biggest problem and solve it. Magic outcomes. But we don’t. Our constraints come into play when we start exploring how we might solve problems. The laws of physics get in the way, first and foremost. The better you get, the harder it is to get better.

In this example, the $10M of leakage is likely to be the aggregate result of a collection of billing issues. Bad addresses, incorrect calculations, pricing mistakes, just as a few examples. Like most problems in the real world, the solution isn’t as straightforward as making one change which drives the totality of benefit. You have to work through a collection of inter-related changes to tackle the problem in aggregate. Then the S-Curve gets you. Resolving all of the sources of leakage is more than twice as hard as resolving half of the issues.

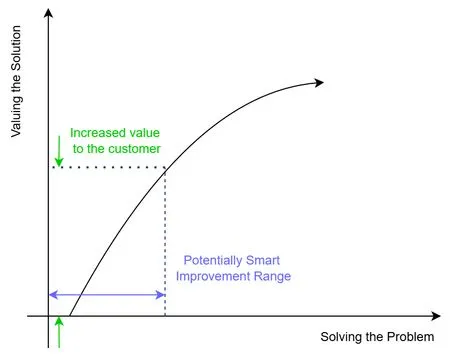

Given that this effort is competing with others for limited capacity, the best use of your limited capacity is to make a smart investment on this problem and smart investments on other problems. This is better than going past the point of diminishing returns on any one problem.

Go back to the article on diminishing returns for the full collection of visuals building the line of reasoning.

Capability Constraints

When I’m helping teams define the work they are going to do to solve problems, we explore not only capacity constraints but capability constraints. Small nimble teams lack scale, large bureaucracies with scale lack nimbleness. The capability gap could be technological, operational, or one of domain expertise.

For any problem you want to solve, between capability and capacity constraints, instead of magically completely solving the problem, what you will instead end up doing is making incremental progress towards solving it. We need to rewrite the problem statement from above to make it useful.

The Problem of… We have revenue leakage of $10M per year because of billing errors

Affects Whom… Customers, customer support, product line general manager

The Impact of Which is… $2M per year in EBITDA at a 20% gross margin

The Benefits of a Solution are… $500K per year in increased EBITDA through reclaiming $2.5M in revenue

While we start by orienting to the scale of the problem ($2M in EBITDA), we have to take into account and talk about what we can accomplish. We form this into a coherent action to address part of the problem. The problem statement helps you with the decision to take this action. When working with teams, I will help to include the problem statement as part of their initiative or program or epic which they use as an artifact to help them make decisions about what to work on and track progress in execution. In this case, the problem statement clarifies an intent to eliminate 25% of the problem.

This container acts as a focusing element for the team to decide if the collection of actions needed to address 1/4 of the problem in its totality is a high priority in comparison with everything else. The team can collaborate to see what the effect of moving the dial on ambition has. Should they tackle 20% of the problem? 50%? Answering the question for this effort requires consideration of the alternative investments being considered and prioritized.

The Size of the Problem Being Solved

Instead of prioritizing based upon the size of the problem in its totality, we have to prioritize based on how much value we are creating. You don’t pay for an all you can eat buffet based on how much food is available, only how much you intend to eat.

There is a huge benefit when designing, scoping, building, and testing, to having a crisp definition of what you are trying to accomplish. You are being unfair to your team if you give them the general direction based purely on the size of the problem.

“We are losing $2M in EBITDA every year due to revenue leakage – try and do something about it.”

You are still being unfair when you give direction without quantification. Now you’re also being unfair to your leadership.

“We are going to reduce revenue leakage by reducing failures to contact the customers.”

This sounds good, you can make a persuasive pitch, even cite the size of the problem. But if you don’t talk about the size of the problem you plan to solve, and only talk about the totality of the problem, you’re not helping anyone.

You lack the information you need to prioritize this work ahead of other work. You lack the information to align the scope of work with the level of ambition, making effective design and execution impossible. All the team can do is build what they want to build – they don’t have a way to answer “did it work?”

Use the The benefits of a solution section of the template to make it clear how much of the larger problem you intend to tackle.

You might find you get what you need.