Why Do Products Fail? – Forgetting that Users Learn

Blog: Tyner Blain

Next up in the series on the root causes of product failure – products that fail because you have ignored the user’s level of experience. The first time someone uses your product, they don’t know anything about it. Did you design your interfaces for new users? After they’ve used it for a while, they get pretty good at using it. How much do you think they like being forced to take baby steps through a guided wizard now?

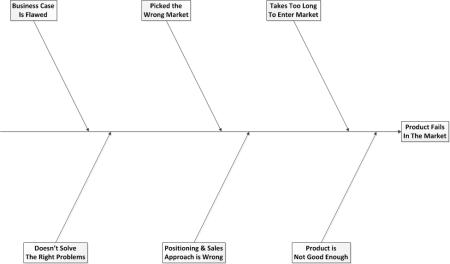

Why Do Products Fail?

Your product launched a year ago. People raved about how easy it is to learn to use your product. Someone posted a video of a toddler using it, it kicked off a meme, you got a nice bump in downloads, and you were thrilled. Now, people are complaining about how impossible it is to actually get anything done with your product. And your main competitor is making hay with their message of cost-effectiveness and efficiency. Sales have dried up to a trickle. What the heck?! You loosen your collar and walk in to explain to your investors why they will be lucky to get half their investment back – much less the ten-bagger your confidently forecast for them eleven months ago.

It sure is good you’re performing this thought experiment before you even build the product, instead of running the gauntlet a year after it launched.

There are many reasons a product can fail. One way to think about your responsibilities as a product manager is to prevent all of them.

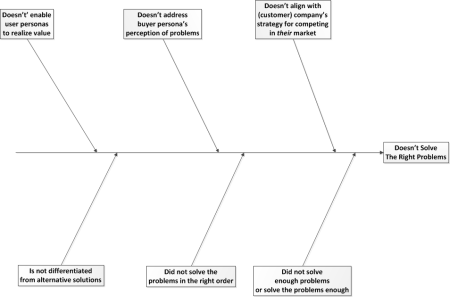

In this series, we are exploring as many of them as we can. In your exploration of the reasons products fail, you started by making sure you’re solving the right problems.

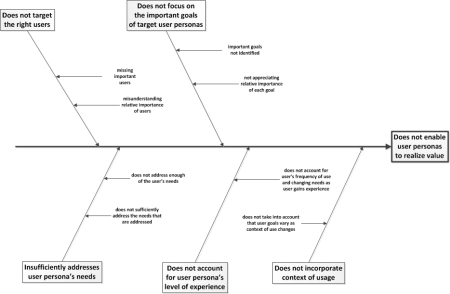

As a firm believer in being user-centric, and making sure you’re delivering value to your users, you’ve doggedly pursued exactly what that means.

You’re confident that

- You’ve picked the right users for your product

- You’ve identified the problems that are important to the right users to solve

- You’ve figured out what you need to do to actually solve those problems sufficiently for those users

What you failed to do was understand that your users change over time.

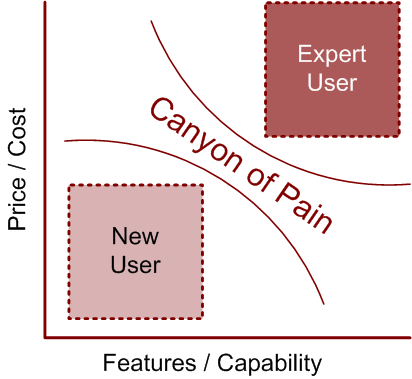

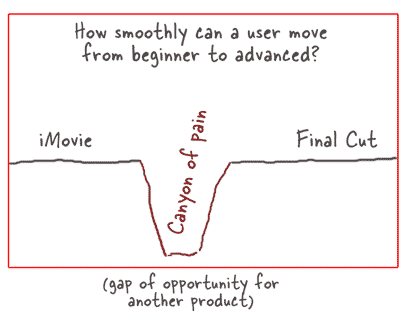

Kathy Sierra’s Canyon of Pain

I wish Kathy Sierra was still writing online. I first came across her canyon of pain model in 2007.

On the other extreme is Apple’s iMovie. It gives you almost no control, but the payoff is high right out of the shrinkwrap. It exceeds my expectations of pain-to-payoff. But pretty quickly, anyone who gets into iMovie–and is bitten by the movie-making bug–starts wanting things that iMovie doesn’t let you control. So… Apple says, “not to worry — we have Final Cut Express HD for just $299″. The problem is, the learning curve jump from iMovie to Final Cut Express is DRASTIC. There needs to be something in the middle, to smooth that transition.

Kathy Sierra, How much control should our users have?

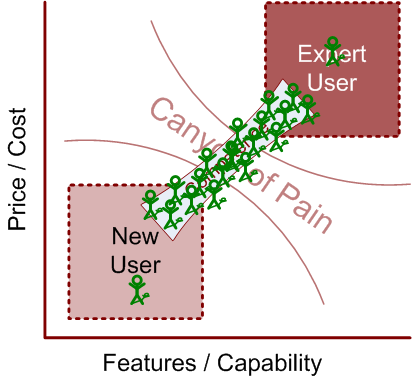

While she uses the above example to describe a market segmentation opportunity, it describes not just the difference between users, but the changes a user goes through over time. Taking an aerial view of Kathy’s Canyon it would look like this:

Most users are competent users. It makes sense – you start out as a new user, until you develop competence, and possibly develop expertise (although few become experts). How many users will use your product for long enough- and invest themselves enough in learning to use your product to truly develop expertise?

Conceptually, you need to build a bridge across that canyon, for your product to meet the needs of your users as they develop confidence (and for the few who become experts).

Learning Curves

This is an artful dance – designing for the competent users – and your personas are likely to represent competent users, since competent users will be focusing on using your product to solve their problems, not trying to solve their problems with using your product. With your focus on making sure you help your users solve their problems, you may overlook the problem that you introduce – learning how to use your product. So, you better make sure you understand the nature of how people develop competence and expertise.

Malcolm Gladwell, in Outliers, builds on Dr. Ericsson’s analysis that it takes 10,000 hours of doing something to become an expert at it (not everyone agrees).

Defining Competence

The first step to measuring competency is to define the model. I am proposing a definition in this article that I suspect will yield insights (to help us manage our products). I was unable to find any quantified definitions of competence, when researching it as part of a client engagement. If you have, or know of a model, please share it in the discussion below this article.

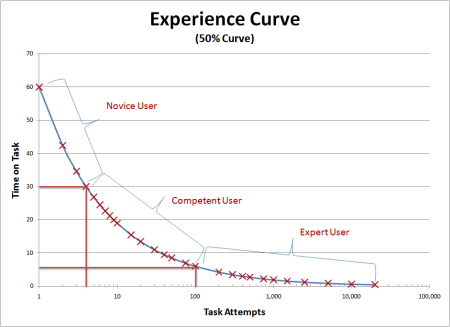

- A competent user is someone who learns to perform a task in half the time it initially took them.

- An expert user is someone who can complete a task in 10% of the initial time.

This definition is guided by an expectation that Alan Cooper’s premise about perpetually intermediate users is true. Being a novice user is a very transient state, and becoming an expert is very infrequent. The goal of the definition is to be able to segment your users and make well-informed design decisions.

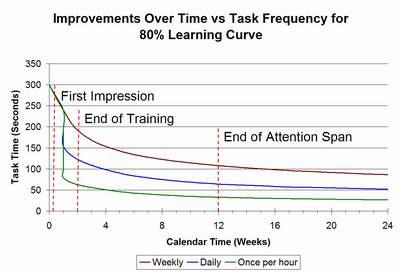

Building on these definitions (and the hypothesis that Cooper is correct), you can model the level of difficulty of task-learning that best represents your product (see the article) to get insight into how rapidly your users will evolve their competency over time. It can impact your modeling of ROI-realization, but more (?) importantly, it gives you insight into understanding how quickly your users will tire of the hold-my-hand-wizards you coded to guide them through your product. As an example, their (measurable) improvement may look like the following:

Of course people are rarely chained to their desks and using your product continuously. Even call-center employees get 5 to 8 minute breaks every hour. So you should develop some insight into how quickly ( in hours / days / weeks) your users develop competence.

The following graph shows how an 80% learning curve overlays a calendar for tasks that happen daily, weekly, and hourly.

[larger image]The graph shows that for a weekly frequency, after 16 weeks, the task time has reduced from 300 seconds to 100 seconds. With a daily frequency, the task time is even lower – about 60 seconds. This graph shows nothing other than converting the academic learning curve graph into one that incorporates calendar time and frequency of occurrence.

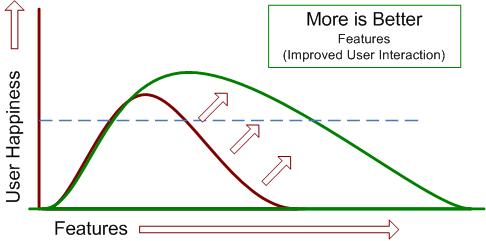

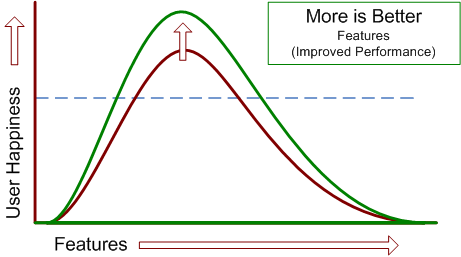

Part of the catch-22 of developing products is that by trying to be all things to people in all-levels of competence, you may try and just add features. Over time, this can really add up. So, you have to figure out the right amount of capability to build into your product. You can play a couple tricks, whipping out your handy Kano analysis skills again, and prioritizing capabilities and features with their characteristics in mind.

Consider the more is better requirements. Think of them in two categories – user interaction improvements, and application performance improvements.

User interaction improvements remove complexity, and make software easier to use. This results in more user happiness from a given feature, and also allows us to implement more features at a given level of happiness (appeasing salespeople).

Application performance improvements don’t create as dramatic of a shift (they don’t make the application easier to use). They do, make it more enjoyable for a given feature set – shifting the curve up.

Summary

Failing to take into account the learning journey that your target users go through is just a more nuanced version of the elastic user problem. The easiest way I’ve found – so far – is to treat “learn how to use your product to achieve their (other) goals” as a user goal, and create a distinct persona that represents your target user while they are a novice.

By analogy, one persona for the caterpillar, one for the butterfly.

If you know of a better way to deal with this as a product manager, please chime in below – this solution is a bit more clunky than I would prefer to use.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[

[ [

[ [

[

[

[