Towards a whole-enterprise architecture standard – 3: Method

Blog: Tom Graves / Tetradian

For a viable enterprise architecture [EA], now and into the future, we need frameworks, methods and tools that can support the EA discipline’s needs.

This is Part 3 of a six-part series on proposals towards an enterprise-architecture framework and standard for whole-of-enterprise architecture:

- Introduction

- Core concepts

- Core method

- Content-frameworks and add-in methods

- Practices and toolsets

- Training and education

This part explores ideas and concepts for a core method for whole-enterprise architecture, and the implied support required within frameworks and methods.

Rationale

The methods we use at present for mainstream ‘enterprise’-architecture are kinda complicated, we might say? In a sense, they probably need to be, to find the right balance between Waterfall and Agile and the like, within a largely predefined scope, usually centred around some form of IT, and usually centred around the ‘business’-level to ‘logical’ level in that model layers of abstraction in the previous post.

But as we move towards whole-enterprise architecture, we need architecture-methods that can self-adapt for any scope, any scale, any level, any domains, any forms of implementation – and that’s a whole new ball-game…

When we look in more depth at the context for whole-enterprise architecture, it soon becomes clear that it’s built on top of a web of inherent conflicts and trade-offs, including:

- machine and human

- certain and uncertain

- identicality and uniqueness

- predictable and unpredictable

- controllable and uncontrollable

- stability and change

- interweaving rates of change, from very fast to very slow

- interweaving lifecycles, from microseconds and less to centuries and more

- shifting timeframes from past to present to future and back again

- shifting perspectives and levels of detail, from vision to strategy to design to implementation to operation, and back again

- a multiplicity of domains-of-interest, each with their own entity-sets, standards, jargon, governance and more

On top of that, to quote Tim Manning on Agile Development:

Design is not a linear process. At the start of a design, it is rare for all the requirements to be known, least fully understood. Design requires a period of discovery and iteration, which incorporates learning, experimentation and even (early) failure. Design, by its very nature, is an emergent process.

The emergent nature of design requires a non-linear approach to development.

Which means that the methods we need for the kind of architecture-work we’re facing now and, even more, into the future, will need not only to work well with any scope, any scale and so on, but must have deep support for non-linearity built right into the core – yet in a way that fully supports formal rigour and discipline as well.

To be blunt, of the very few current ‘EA’-frameworks that provide a method at all, probably none are anywhere near competent for this task. If we’re going to satisfy those requirements, it seems pretty certain that we need to go right back to first principles, and start again from scratch.

But where do we start?

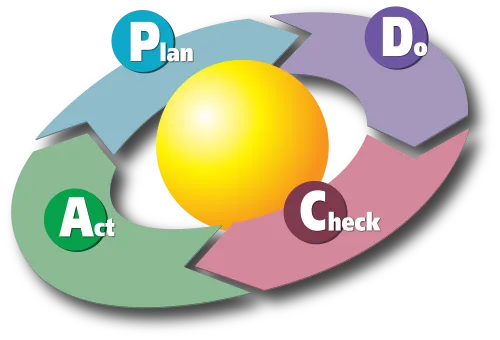

Enterprise-architecture is deeply engaged in continual improvement within the organisation and enterprise, so one place to start could be with the classic PDCA-loop – Plan, Do, Check, Act:

And it’s not that far different from what we have in EA already. For example, the TOGAF ADM (Architecture Development Method is in effect a variant of a PDCA-loop: the ADM Phases B-D are sort-of equivalent to the PDCA Plan phase, ADM Phases E-G the Do phase, ADM H a rather incomplete Check phase, and ADM Phase A a largely-hardwired Act phase. So with some significant but doable amendments, it might at first seem as if we could perhaps hack something like the TOGAF ADM to do the job we need here.

Yet the reality is that PDCA doesn’t go anything like far enough for what we need. In particular, it doesn’t really touch all that much on the human aspects of change – and EA is a discipline that’s often been described as ‘relentlessly political’, so the human-factors are kinda important here…

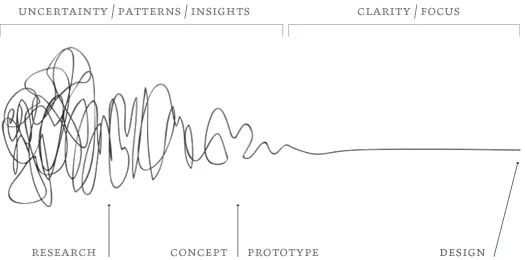

Hence a perhaps better place to start would be with what a generation of designers now would describe as ‘the Squiggle‘ – a visual map of the inherent-uncertainty in the design-process:

It starts with the initial seed of the idea – the purpose of the design-project. There’s then a wild swirl of uncertainty, iterating back-and-forth across many different options, opinions and more, before slowly settling out towards a distinct plan for action, and then putting that action into concrete form in real-world practice.

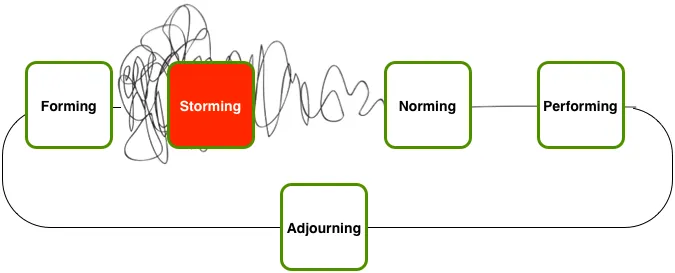

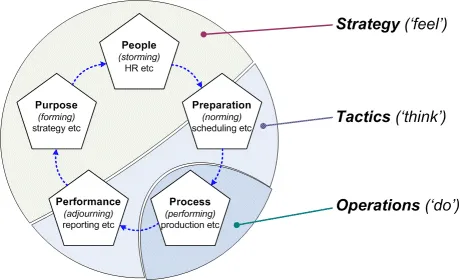

Given that, there’s a lot of immediate similarity with Bruce Tuckman’s classic Group Dynamics project-group development and project-lifecycle sequence – Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing. The model provides further clarity on what happens in the Squiggle sequence, by including strong emphasis on the importance of the human-oriented Storming phase – in fact includes clear warnings about the very real risks that arise from attempting to bypass that phase, as tends to happen with unaware usage of a PDCA-type model. And it also adds an optional extra phase – Adjourning – that focusses on benefits-realisation and lessons-learned from the previous work in that project-sequence. This then connects back to the purpose from the initial Forming phase – converting the original linear sequence into an iterative loop. If we’re willing to accept a project-like concept of EA-activity – whether in linear form, or as an iterative loop – then the Tuckman model fits well, especially when we connect it with the visual map of the Squiggle:

For many of us, though, describing everything in EA as a project would not seem right. After all, one of the key concerns for EA is that it needs to be understood as a business-capability in its own right, rather than just ‘some stuff we might use within projects’. And timescales for EA-activities can vary enormously, from mere hours to multiple years and more. To resolve this, we can usefully turns to a much older version of the same kind of pattern, namely the classical Chinese Five Elements – Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water. What this adds to the picture is fractality – the same pattern repeating indefinitely in self-similar ways, but also optionally nesting in recursive fashion, to any depth, any scale. And with perhaps more business-oriented labels for the phases, it gives us an overall structure for a method that matches well enough with the way that we actually work in EA and related disciplines:

[image: five-elements-as-purpose-etc]

In which case, we’ll use this as a proposed method for our framework for whole-enterprise architecture – and expand on how this would work in practice in the following ‘Application’ section.

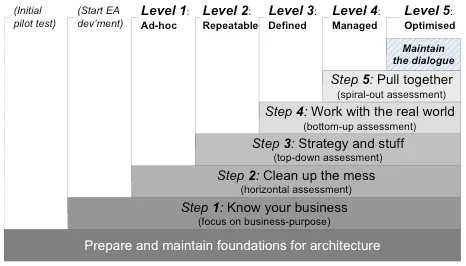

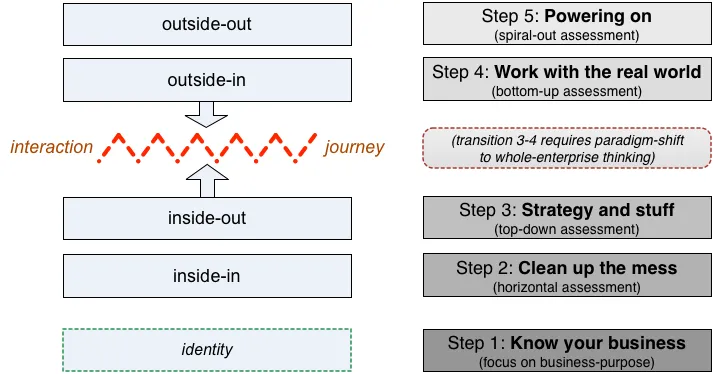

But even given a structure for method, what do we actually do? What would guide choices about what architecture-issues to tackle, and when? One suggestion here is a maturity-model that I’ve used for some years, loosely modelled in the well-known CMMI structure, but with an emphasis less on the ‘maturity-levels’ currently achieved, but more on the steps that we need to take to move from one maturity-level to the next:

Each of the steps presents and makes use of what are actually quite different theories of the enterprise:

- Step 1 (‘Know your business’): There is an underlying human-story – enterprise as ‘a bold endeavour’ – that underpins decision-making and choices for capabilities and services within the enterprise.

- Step 2 (‘Clean up the mess’): There are clear and identifiable rules that determine clean-up activities such as simplification and de-duplication.

- Step 3 (‘Strategy and stuff’): Strategic choices – however complicated – can be determined and implemented via algorithms and analytics.

- Step 4 (‘Work with the real world’): The real-world is inherently uncertain and ambiguous, but actions can be guided by patterns and probabilities.

- Step 5 (‘Pull together’): When faced with uniqueness or the not-known, the most useful guidance is provided by principles that anchor back to the original deep-story.

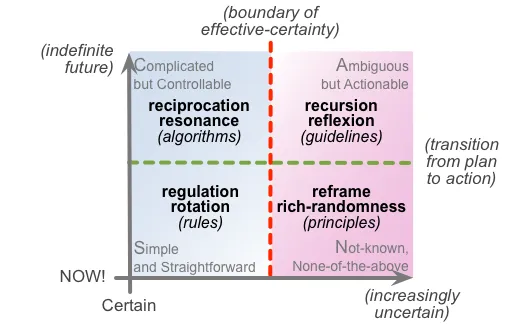

Those ‘theories of the enterprise well with the decision-tactics outlined in the SCAN framework for sensemaking and decision-making:

And with the ‘perspectives-set that we saw in the previous part of this series:

The architecture-development is not literally step-by-step in that sequence: step-by-step is what we’d prefer to do, and should do wherever practicable, but Reality Department so often gets in the way towards that ideal! What the model does warn us, though, is that activities for each step in effect depend on completion of the respective parts of the ‘previous’ step(s): hence each time that we do have to do things out of step, we’re creating technical-debt – literal or metaphoric – that we’ll have to come back to and clean up again later.

(For a more detailed overview of the maturity-model, see the slidedeck ‘Stepping-stones of enterprise-architecture‘ on Slideshare.)

Application

From the above, we can derive suggested text for the ‘Methods’ section of a possible future standard for whole-enterprise architecture. Some of the graphics above might also be included along with the text.

– Role of method: The purpose and role of the method is to support iterative sensemaking and decision-making within architecture-development for any or all of an entire enterprise or beyond.

– Scope of method: The method must be able to self-adapt to any scope, any scale, any level, any domains, any forms of implementation, and for any architectural-type purpose within the respective enterprise. In part, this means that there needs to be a distinct phase within the method to identify the scope and purpose of the current iteration of the method.

– Human-oriented focus: We define ‘enterprise’ as ‘a bold endeavour’ – an inherently human construct. Everything else in the enterprise – content, implementation, whatever – is subordinate to this human need and drive. In part, this means that there need to be distinct and explicit elements within the method that work with and acknowledge human feelings as well as functional system-behaviours and outcomes.

– Explicit support for conflict-resolution: One consequence of a human-orientation for the method is a necessary acknowledgement of the inevitability of conflict and ‘Storming’ between stakeholders, and about matters of design, intent and more. In part, this means that there need to be explicit elements within the method that identify, work with and provide resolution for such conflicts.

– Support for any architectural-content: The method must to be able to work with and adapt to any architectural context and need. As a result, it must be able to support any type of implementation-content, at any level of detail. (This is in sharp contrast to many current ‘EA’-frameworks, which prioritise IT over everything else, and often render ‘invisible’ many other types of architectural elements.) This requirement for content-adaptability would typically be supported by content-specific ‘plug-ins’. (More detail on this in Part 4 of this series.)

– Context-first, not content-first: Because the method needs to be able to work with any type of implementation-content, it must itself be content-agnostic. We might describe this as ‘context-first, not content-first’. (This is in sharp contrast to most current ‘EA’-frameworks, most of which prioritise content over context, and often assert or assume – such as via the ‘BDAT-stack‘ – that every context will always need an IT-based ‘solution’.)

– Architecture and governance: Governance is an essential aspect of architecture-development, design, implementaition and deployment. In part, this means that the architecture-method needs to embed and apply change-governance, to guide all of the stages throughout the change-lifecycle and beyond. Since these will changes will have differing types and levels of complexity, lifecycle and other factors, this will necessitate support for a range of governance-types – from ‘waterfall’ to ‘agile’ and more – this implies that governance-support within the method would more take the form of ‘metagovernance’, from which any required form of governance could be derived.

– Closure and continuous learning: The method, on completion of an iteration, needs to support assessment of benefits-realisation – to link back to the original purpose of the iteration – lessons-learned – to drive continual-learning and overall situational-awareness.

– Support for fractality: The method needs to be able to support architectural-explorations across any scope, scale, domain and more. Such explorations will often occur as a result of questions arising from within other currently-active explorations, giving rise to a concept of recursive-nesting or fractality of architecture-iterations. The method must therefore be able to support fractality of itself within itself, to any required depth of nesting.

– ‘Start-anywhere’ principle: The method needs to be able to ‘start-anywhere’, apply to anything, any scope, any level and so on. This means that the method must not embed any ‘hard-wired’ requirement for an assumed mandatory start-point for exploration. (This is in sharp contrast to most current ‘EA’-frameworks’, which typically assume or demand a whole-organisation or whole-of-domain scope and start-point.)

– Applicability and usability: One of the core concepts of whole-enterprise architecture is that architecture is everyone’s responsibility – not solely the province of those who describe themselves as ‘architects’. Because of this, the method needs to be usable by anyone, to any required level of complexity: it must be simple enough to be usable by an inexperienced trainee in frontline-operations, yet also be powerful enough to satisfy any professional needs. The most probable means to accommodate these requirements is a combination of a conceptually-simple frame, coupled with the power provided by fractality and by content-plugins, as described earlier above.

– Implied need for architecture-repository: The probable phased nature of the method, and the required support for fractality and for lessons-learned and suchlike, implies a need for some kind of shared-repository to store information for use and re-use in other phases and iterations, and for historical-analysis, simulation-development, cross-domain review and more. This hypothetical repository may take any appropriate form, from handwritten notes to photographs of whiteboard-sessions to full purpose-built toolsets and more. (More on this in Part 5 of this series.)

From this, and from the descriptions in the Rationale section above, we could propose a method based on the Five Elements model, which we could summarise visually as follows:

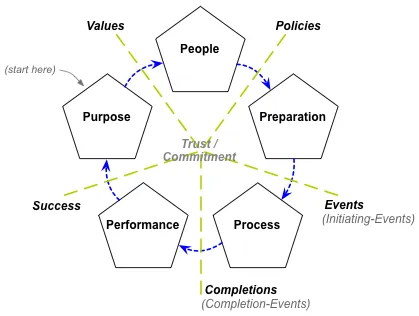

Or, in terms of transitions between the respective phases of the method:

We could summarise the simplest level of the steps or phases as follows:

– 1: Purpose ['Forming'; Why]: Identify the underlying reason and scope for the session.

- What is the question (or ‘business-question’) that this architecture-session should address? What is the purpose here?

- What is the context for this session? – its scope, scale, level, domain(s) etc.

- What are the expected or required outcomes (if any)? for this session? What would be the expected guiding indicators of success or not-success for this session?

- Example action: Start with ‘the problem’, then apply Five Whys or equivalent to identify: why this is important; what would (probably) happen if this is/is-not addressed; how this aligns with the big-picture for the overall shared-enterprise

- [Store in repository: discussion-notes, whiteboard-images, initial-requests etc]

– 2: People ['Storming'; Who]: Identify the people-issues in context of the session.

- Who are the stakeholders for this question? (including the ‘project-sponsor’, if any)

- For each stakeholder, explore:

- What is their stake in this question? Apply Five Whys or equivalent to identify: why this is important to them; what would (probably) happen for them or others if this question is/is-not appropriately addressed; how/why they do/do-not align with the broader shared-enterprise and this organisation’s role within it

- What are their respective ‘response-abilities’ in this? Apply RACI, SEMPER or similar to identify: RACI positioning, power-issues (power-with vs power-against), and skills competencies and knowledge etc.

- How should we engage them in this question? Assess needs for communications-plan, engagement-plan etc

- What is the story that would link and unite all of these stakeholders and shared-supportive action within the shared-enterprise, in context of the scope of this session?

- Where conflicts between stakeholders either exist or are probable or possible, prepare for and apply appropriate conflict-resolution methods.

- [Store in repository: discussion-notes, whiteboards, stakeholder-lists, RACI maps, SEMPER-assessments, engagement-plans, 'marketing'-materials etc]

– 3: Preparation ['Norming'; How]: Prepare for action to address the needs in context of the session.

- What needs to be in place before taking action on this question?

- What are the constraints on ‘just enough detail’ for preparation on this question? (This will usually be some combination of time, budget, people and/or risk-appetite and/or perceived-emergence.)

- Given the constraints, use personal judgement(supported by guidelines where appropriate) to iteratively select and apply assessment-, sensemaking- and design-tools to make sense of and plan for the required activity.

- (These would include any appropriate content-frame or assessment-checklist that can be linked to the method, as described in Part 4 of this series. In my own case, these might include SCAN, on complexity and inherent-uncertainty; SCORE, on capability and effectiveness; Backbone & Edge on dependability and stability; Maturity-Model on action-competence; Enterprise Canvas suite on service-design and service-mapping; Actor, Scene & Stage for story-development; and various logistics tools for resource-preparation. Other architects would no doubt use other frames, according tpo their experience, preference and need.)

- Where appropriate, optionally partition the exploration into distinct time-horizons such as ‘current state’, ‘intermediate state’, ‘future state’ and suchlike.

- Identify conditions at which ‘just enough detail’ will be achieved, and ‘just enough action’ may be enacted.

- [Store in repository: discussions, whiteboards, plans, models, action-record templates and metrics etc]

– 4: Process ['Performing'; Where / When / With-what]: Enact the intended action to address the needs of the question for this session.

- Follow the current plan of action.

- Record outcomes of action on action-records, metrics, etc.

- Reassess the plan on-the-fly as required, using tools such as OODA and SCAN for near-real-time reassessment: sense, make-sense, decide, act.

- Repeat until the required end-condition is reached.

- [Store in repository: action-records, metrics, run-time reassessments etc]

– 5: Performance ['Adjourning'; Success]: Close the session, and prepare for any succeeding sessions.

- What was achieved in response to the question for the session? What benefits were realised, relative to the layered purpose? What were any lessons-learned?

- Optionally, apply an extended-After Action Review [AAR] to identify:

- what was supposed to happen? (Preparation)

- what actually happened? (Process)

- what was the source of any difference? (Performance)

- what can I learn from this, to do differently next time? (Purpose)

- what can we learn from this, to do differently next time? (People)

- Identify:

- questions to be addressed in future sessions

- personal commitments to change, or skills to be developed

- collective commitments to change, or shared-skills to be developed

- information and insights to be forwarded for overall situational-awareness in the organisation and/or shared-enterprise

- [Store in repository: AAR records, questions, commitments, amendments to action-records and metrics, etc]

– Support for fractality and non-linearity: Note that the method / pattern is recursive and fractal, and optionally non-linear:

- At any point within a session:

- identify an issue that needs to be addressed, on its own terms and within its own scope etc

- store any status-information for the current architecture-assessment session

- start a new architecture-assessment session, using the new issue as its Purpose

- on completion of the ‘child’-session, return to the ‘parent’ session, using information as updated in the ‘child’ session

- At any point within a session:

- store any status-information for the current phase of the current session

- jump back temporarily to a previous phase of the current session

- warning: do not ‘jump forward’ in a session without coming back later to complete any incomplete previous phases; in particular, do not attempt to skip the People/Storming phase, as doing will almost invariably cause even stronger Storming later…

- At any point within a session:

- store information that may be potentially-relevant to a future phase in the current session, and/or to another later session

- Cycles may be nested to any depth, and may be interrupted at any point – take care at all times to keep track of the current status of each active session!

– Session duration and complexity: Sessions may be of any duration, nested to any depth as required. At its most minimalistic, a session might literally last a matter of seconds, using the Five Elements tag-lines as a quick real-time checklist. At a much larger scale, a nominal session could be the approximate equivalent of a multi-year TOGAF8-style IT-landscape rationalisation, containing a multitude of nested child-sessions within the overall architecture-development session, all of the sessions using the same Five Element pattern. Complexity of a session is largely a matter of choice and professional judgement, dependent on the requirements of the Purpose-question, the scope of stakeholders, the frames used in preparation, and the type of architectural action undertaken: again, this may be anywhere from minimalist to a massive multi-disciplinary project or programme of work. The key point here is that neither duration nor complexity are hardwired into any part of the Five Elements pattern: they are derived from how the pattern is used, not from the pattern itself.

The above provides a quick overview of a fully-fractal method that we could use for sensemaking, decision-making and architecture-development in a whole-enterprise architecture. (I do know that it’s not complete enough for any kind of standards-proposal! – this is really little more than a strawman to use as a base for further discussion, exploration and critique.)

We’ll move on now to explore some ideas about how we could link specific content – or, more often, information about content – to the method, to guide architecture, design, implementation and real-world deployment.

In the meantime, any further comments so far?