Sensemaking: Down in the dungeons

Blog: Tom Graves / Tetradian

Following on from the previous post ‘Sensemaking: Into the void‘, what’s a good everyday analogy or example on how to develop our skills in sensemaking and strategy? In particular, how to understand, apply and use the ‘sense, make-sense, decide, act‘ loop that underpins how to get best use out of the toolset?

One option could be the good old game of ‘Dungeons & Dragons‘ (‘D&D’):

And yes, I’m serious about that. To quote from Simon Wardley‘s post ‘Dungeons and Dragons vs the art of business strategy‘:

“For anyone under the illusion that business is some bastion of strategic play then can I suggest you spend a few minutes either watching an experienced group play D&D or an organised raid on WoW [‘World of Warcraft‘]. Those people tend to use levels of strategic and tactical play that businesses can only dream of.”

So how does this link with Five Elements, and the rest of the toolkit that we’re developing at present? Another quote from Simon Wardley might help at this point:

“business strategy is normally a tyranny of action (how, what and when) as opposed to awareness (where and why)”

(Note that for this context, Simon’s ‘Where’ is, in effect, an aspect of ‘Why’ – see my post ‘Why and Because‘ for more on that.)

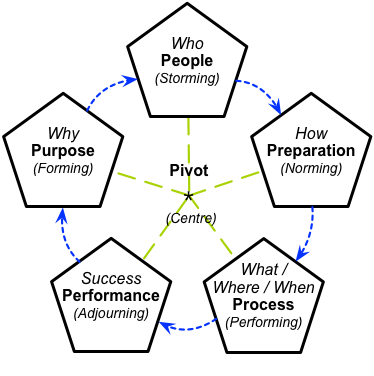

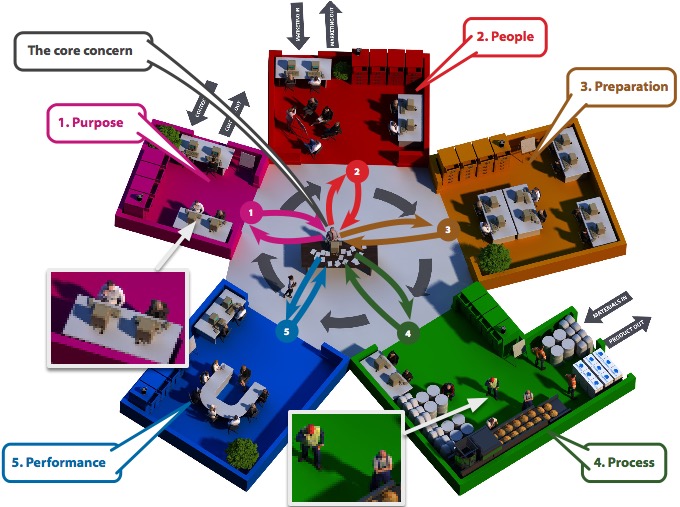

If we cross-map that statement of Simon’s onto the basic Five Elements model:

…and also:

…then what he’s describing as “business strategy [as] a tyranny of action” is, as he warns, short-term tactics misunderstood as ‘strategy’ – otherwise known as Not A Good Idea…

In other words, we need to do longer-term strategy as strategy, near-term tactics as tactics, and real-time operations as operations – and not mix them up. All whilst learning from from everything that we do, and keeping on-track to purpose as well.

How to do that?

Well, that’s where games such as D&D come into the picture.

In another part of that post, Simon Wardley splits the key requirements for development of strategy and the like into four key areas: maps; capabilities and roles; team play; and preparation. It’s worthwhile exploring each of those in a bit more detail, in context of the Five Elements model.

— Maps

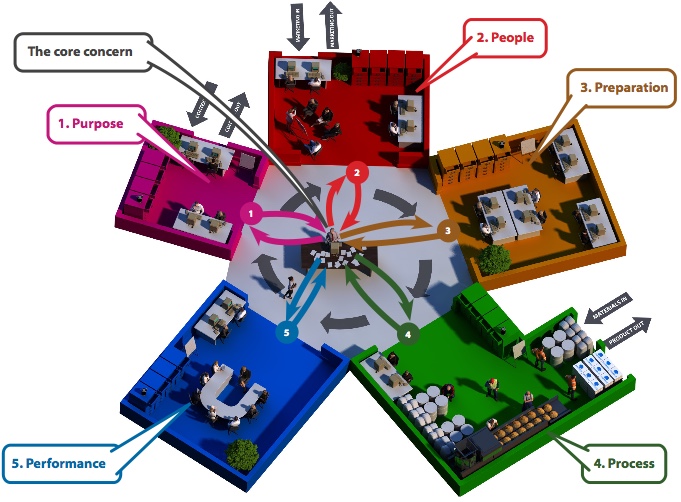

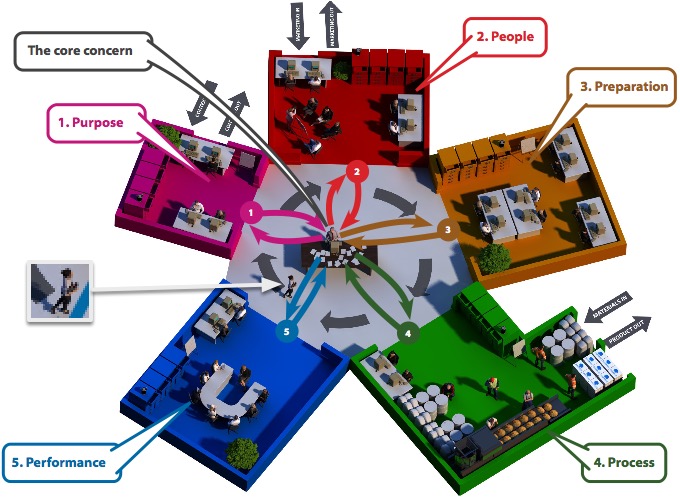

In his online-book on maps and mapping, Wardley argues that the basic elements of any map must include “ visual, context specific, position of components (based upon an anchor) and movement”. Although many of the tools that we’d use with Five Elements do fit that definition, Five Elements is not quite a ‘complete map’ in that sense. Instead, it’s more like the exploration-space of a board-game – or a game of Dungeons & Dragons:

Yes, it’s visual, it has components and positions, and it does have explicit movement – as we’ll see in a moment. It doesn’t, though, include a fixed anchor-point as such – the central table in the atrium is perhaps the nearest equivalent to that. And, by intent, it is not context-specific: instead, identifying the applicable context for each session is itself a key part of the play. The visual space is laid out like the departments of an organisation, but that’s mainly to give a sense of familiarity – not as a constraint on the contexts for which the game can be used.

— Capabilities

I interpret the term ‘capabilities’ to mean ‘ability to do work’. So in that sense here, the capabilities for the game are the methods and guidelines for play, plus the tools in the toolchests in each room – the colour-coded ‘filing-cabinets’ in each of the rooms. (There may also be another small toolchest in the atrium itself: I think there is, with tools to guide the play, but there’s still some argument amongst our team about that.)

I won’t go into depth on those here, but there’s more on ‘how to play’ in the post ‘Methods for whole-enterprise architecture: Keep it simple‘. For the tools in those toolchests, we’re starting off with a subset of ‘the inventory‘, but will extend it to the full set as soon as we can; and players will be able to plug in their own tools anyway – much like ‘add-ons’ for a D&D-type game – so in principle the overall toolset could be almost infinitely extensible, to cover any type of context in any depth that players might need.

— Roles

We see three direct, active roles in this: the Explorer, the Guide and the Scribe. There’s also a more passive, indirect role that at present I’ve labelled as the Local (though I do need a better term for that).

The Explorers are the people who are actively pursuing the quest – in other words, aiming to resolve the initial question or concern. In the Five Elements ‘gamespace’ these are represented by this figure:

…who’s shown beside the table at the centre of the atrium – in other words the place where collating and overall sensemaking will take place. As indicated by the coloured arrows, the Explorers also travel back and forth between there and the ‘rooms’, to gather ideas, insights and information:

As I’ll expand a bit more when we get to ‘Team-play’ below, there’ll typically be between one to a dozen Explorers for any given Five Elements session. They’ll need a diversity of skills and strengths, and, often, most or all of the attributes that (to quote a Wired article on D&D) will help to form the core of every Dungeons & Dragons character: strength, constitution, dexterity, intelligence, wisdom, and charisma.

The Guide has much the same role as the ‘Dungeon-Master‘ in a D&D game: to keep on-track to the rules of the game itself, so as not to get lost down the rabbit-hole of exploration. In the Five Elements ‘gamespace’ the Guide is represented by this figure:

…who’s shown here off to the side of the atrium, observing the Explorers, and following them wherever they go:

The guide does not take any active part in the exploration itself, but instead provides guidance on how to do exploration, and how to avoid traps and antipatterns and suchlike that can put the process of exploration at risk. The guide will sometimes offer questions about a context, and what to look for in that context, but in general will avoid providing any kind of ‘the answer’ – if only to minimise the ever-present risk of ‘solutioneering’.

The Scribe has the task of recording what’s going on, what ideas and information are captured, and so on. Every exploration needs a scribe, a recorder, a story-teller, somewhat off to one to one side from the exploration itself – able to be ‘objective’ in that way that the explorers themselves often can’t.

In a sense it’s sort-of optional – it’s recommended that someone on a team has this as a distinct role, but it’s not mandatory, especially in smaller teams. In some cases the Guide can also take on this role, to free up all of the Explorers for the exploration.

Because it’s an optional role, there’s no separate representation for it in the Five Elements ‘gamespace’, though in a sense it’s implied by the clipboard carried by the Guide.

The Locals are not part of the exploration-team, but instead are the people, things and information that the Explorers meet up with during their exploration of the respective room. In the Five Elements ‘gamespace’, the Locals are represented by figures and objects such as these:

…which are shown as the ‘contents’ of the rooms, engaged in typical tasks for the respective room:

At first it might seem that this is a bit different from D&D, because the Locals here are not orcs or dragons to fight, but people and contexts that, if we ask the right questions, can provide us with the information and insights that we need. In a sense, though, the metaphor does still hold, because the Locals can help us return from our exploring with real treasure, if we ask them in the right way.

— Team play

The game-play – or, more specifically, the roles in the game – can vary somewhat dependent on the number of players in a session of the game.

In a solo-game, the player would have to act as Explorer, Guide and Scribe – which can be quite a challenge. In practice, we’d typically use step-by-step instructions in a book or app to act as the Guide, and pre-printed forms as a basic form of the Scribe. The player can then switch between reading the instructions for each part of the exploration, as the Guide; following the Guide’s instructions, as the Explorer; then stop to record the results, in the role of the Scribe. Solo-play is often the only option available, but we need to note that, given the role-switching, it can quite a lot be slower than with even a small team, and is more at risk of falling into ‘echo-chamber‘ traps and the like.

In a small-team game, with 2-3 players, there are enough people to take on distinct roles as Explorer, Guide and Scribe. Again, a book or app can act as the Guide, and forms and like provide some of the services of the Scribe; but the group is large enough that at least one of the team can pay distinct attention to those support-tasks whilst the exploration is going on. For a small-team, it would be usual to switch between the roles at various times during game-play, so as to make the best use of the diversity of experience and suchlike in the team.

In a larger-team game, with up to a dozen players, there should be enough diversity to cover all potential needs. The role of Guide, and even the Scribe, might well be taken on by external consultants, or by other people ‘outside’ of the team itself. The risk with a larger group is a stall into argument or ‘analysis-paralysis’, or dominance-games such as the HiPPO (Highest-Paid Person’s Opinion): the Guide will need sufficient skills to marshal the team, keep them on track, prevent premature ‘solutioneering’, and keep the whole team focussed on the question at hand.

The game-play is much the same in each case. Following the advice from the Guide, the team will ‘move’ from room to room, and use the tools in each space to capture ideas information and insights about the concern at hand. For a simpler game, there are default tools for each room, which cover the enough of the basics for any typical exploration, and feed onward from one room to the next in a clockwise step-by-step cycle. In more advanced game-play, the moves can be more freeform, and any from all manner of different tools can be used in each room, selected by keywords and the like from the conversation taking place between the Explorers – but the Guide and Scribe may need some skill and experience to catch those keywords, particularly within the back-and-forth real-time dialogue of an actively-engaged larger group.

The most important work, though, happens around the metaphoric table in the centre of the atrium – collating, curating and real-time sensemaking. It’s important to note that the tools exist only as a support, a form of guidance, a checklist for questions that need to be asked: the real work, and the real insights, arise always from the Explorers themselves.

— Preparation

There’s not much preparation that we’d need for a Five Elements game, beyond the usual pen, paper, whiteboard and the like, perhaps some forms for information-capture (the documentation side for the tools), and maybe some materials for guidance – such as this blog-post, or our upcoming book. The Guide – if there is one – should also ensure that that the right sets of tools are available and ready for gameplay, suitable for the maturity-level of the respective team.

Other than that, the only preparation we’d need is to run into the space with a question, and go questing! (It’s also wise to set a time-limit, or some equivalent constraint about ‘just enough detail‘, to say when to end the game – otherwise there would, as usual, be a risk of falling into interminable ‘analysis-paralysis’.) The aim is that the space, the rules, the tools and the Guide can help elicit an exploratory dialogue from which useful ideas and insights can arise.

Anyway, that’s it for now: Dungeons & Dragons as a metaphor or analogy for sensemaking with Five Elements.

Any comments, anyone?

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.