Saying NO during major organizational change actually makes things happen

Blog: Changefirst Blog

By Audra Proctor, Head of Learning & Development, Changefirst

Tweet

Subscribe to Changefirst blog alerts and newsletter

“The volume and complexity of business change continues to increase, and organizations cannot risk the negative impacts of not executing their business critical changes.”

This is a paraphrase of what seems to be the typical first paragraph of most change management articles and white papers I’ve been reading the past few months. Of course, this sits well within our sweet-spot at Changefirst, as the focus of our work is on helping major, global organizations build their capacity to execute change initiatives to release business value.

In particular we are supporting enterprises and employees who are also time poor, with a digital end-to-end implementation focused solution, which can get project teams up and running in 48 hours, instead of 48 days! However, in this blog I want to talk about the other side of building change capability – which is managing the demands being made on that capacity.

In our experience, leaders are often accused of operating as though there is unlimited energy and good-will in the organization to accommodate change. They can believe so strongly in the soundness of a change solution that conducting an assessment of the organization’s ability to absorb the change impact is simply not a part of the discourse.

For me, the term “major change” has two meanings:

1) It refers to the complex structural, organizational, technological or cultural change decisions being requested by an organization

2) It refers to the adjustments and shifts people need to make to their aspirations, attitudes, behaviors and ways of working to accommodate the change decisions and remain effective.

The bottom line is there are so many changes which are major in nature that people can be overwhelmed by their cumulative impact, such that potentially the biggest risks to successful execution is actually this perpetual loading.

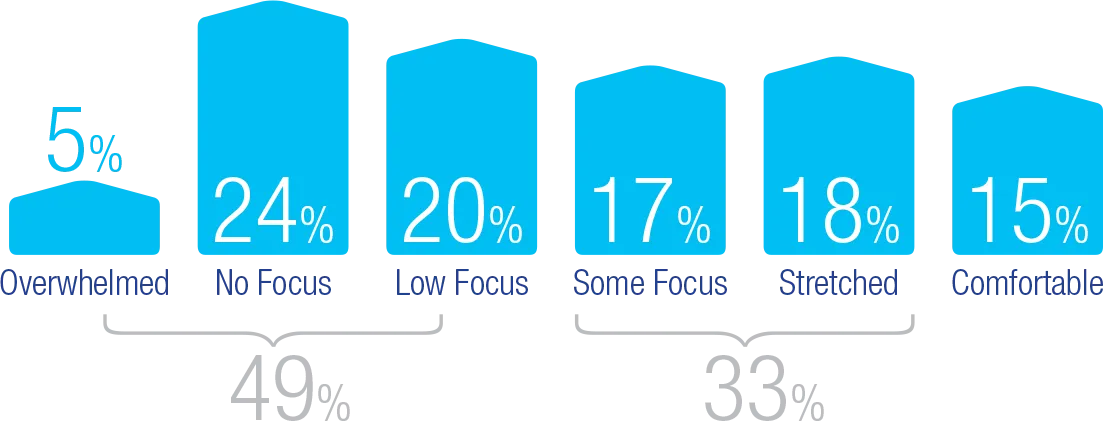

Our own data (see figure 1) showed that almost half (49%) of people contributing felt that their organization was already overloaded by change and lacked the focus to get business critical change projects done.

Figure 1

All of this creates an environment where enterprises and employees believe that time is a very precious resource and the possibility of being overwhelmed by work is always just around the corner. In fact, in some cases it is here right now. Solutions that can offer convenient help when and where people need it are likely to be prized over more fixed offerings that involve travel and days away from work and family.

Real evidence of perpetual loading which I see and feel on the ground is: the struggle to recover capacity to deliver day-to-day efficiency and quality targets; an inward focus on managing change rather than an outward focus on customers the changes are designed to serve; continuous state of upheaval and chaos created by people changing positions and lots of coming and going of key decision makers.

So what can leaders do now?

Do nothing and hope is really not an option as employees are already struggling to assimilate change without signs of dysfunction, and organizations (as a collective of its employees) struggle to deliver change initiatives effectively enough to release the benefits intended.

Research like the study by Sean Covey, Chris McChesney and Jum Huling (authors of The 4 Disciplines of Execution) affirms this. The study of over 1,500 projects showed that organizations with 11 – 20 key priorities (over and above operations) didn’t achieve any with excellence. Those that focused on 4 – 10 priorities manage to achieve 1 or 2 with excellent results, while those focused on 2 or 3 priorities manage to achieve all of them with excellent results.

Rapidly increasing capacity is not really that rapid as organizations struggle to create the infrastructure needed to embrace new approaches to learning and tying learning to application.

The real call to action here for leaders is to say NO. No is one of the smallest words in the English language, yet most of us have trouble saying it. The first question we ask Executives initiating change is, “What are you going to give up, so this change has a chance of success?” Saying no starts at the top of the organization with the most senior people on a change initiative helping people understand what requests they de-prioritize. The best leaders and managers know that they have to lead the way in saying no to things that are out of scope, because when they do say no, and make it stick, key business imperatives gain momentum.

Interestingly, in times of turbulence and change, the things we need to be saying no to would have historically fueled our feelings of control, comfort and confidence. We need to be saying no to things that we are competent to do and that takes less of our capacity to accomplish. Often we need to prioritize those initiatives which require us to learn and do new things.