Is culture-change the same as software-change?

Blog: Tom Graves / Tetradian

Should we approach culture-change as if it’s the same as software-change? At a current conference, James Archer seemed to interpret Alex Osterwalder as saying just that:

- jamesarcher: Company culture can be methodically designed, built, and tested almost like a software product. #bos2015 @AlexOsterwalder

To which – probably no real surprise to people who know me – I kinda fulminated:

- tetradian: Oops… a really, really fundamental error, as wrong as the delusion of ‘engineering the enterprise’….

James Archer seemed somewhat dismissive of my retort:

- jamesarcher: I used to think the same, but have since had enough experience to watch it happen (and manage it myself as well).

I tried another tack to make the point:

- tetradian: a simple question: do you want your social-relations/purpose viewed as “like a software product”? – if not, consider again… // yes, there are some ‘designable’ elements: but if we think it’s something we can control, we’re deluding ourselves, dangerously

To which James Archer again came back, replying to the first of my two Tweets just above (“consider again…”):

- jamesarcher: if you were the CEO of a company with a dysfunction culture, would you not plan to shape it a different and intention way?

And to the second (“deluding ourselves, dangerously”):

- jamesarcher: I’d consider it more dangerous to think of culture as a dangerously untouchable part of our lives.

Both of which points are valid and true, of course – in their own way. But there’s a huge, huge ‘It depends…’ sitting in there – and if we miss how important it is, we’re likely to cause huge damage to the respective culture, without being able to understand what’s happened, or why. I summarised this in a quick Tweet, though recognising that that comment wasn’t enough on its own:

- tetradian: of course, but software is tame-problem, done to; culture is wild-problem, done with – v.different! will blog on this

Which, in turn, brings us here – where we can look at such matters beyond the max-140-chars constraint of Twitter…

To start this off, let’s make an assertion here: that pretty much by definition, culture-change demands that we address the whole context of that culture. There are a fair few ‘It depends…’ aspects to that, of course, but it’s probably close enough for now – particularly for what “the CEO of a company with a dysfunction[al] culture” would need to know before trying to change anything.

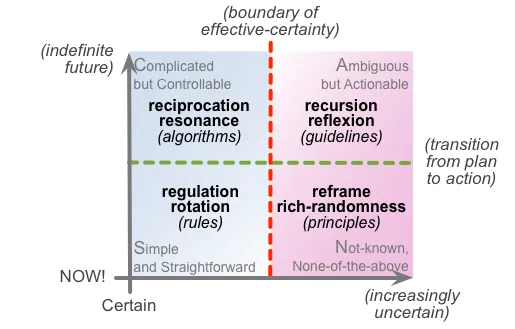

Given that, it’s probably simplest to set the scene a couple of SCAN cross-maps. The first summarises the types of tactics that we’d typically best apply to different ‘domains’ of the context:

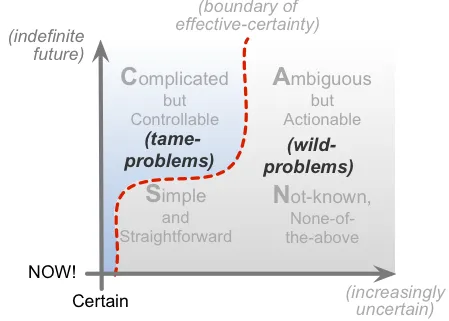

And the other crossmap summarises whereabouts in a context we’d typically come across tame-problems versus wild-problems:

Some of that context – emphasis: some of that context – will indeed be amenable to tame-problem tactics: rules, regulations, predefined ‘solutions’ and suchlike. The idea with tame-problem tactics is that if we do the same things the same way with everyone, then we’ll get the same result from everyone too. And it does work – in some parts of the context. But not all – and that’s the point we need to note here.

In the parts of the context where wild-problem elements predominate, we cannot use tame-problem tactics. If we do attempt to do so, we’ll discover very quickly why the perhaps-more-common term for wild-problem is ‘wicked-problem‘ – because things can turn wicked on us very fast indeed. And the more we try to ‘control’ the culture, the worse it’ll get.

The key point to understand with all wild-problems is that they’re on the far side of the boundary of effective-certainty. Which means that if we do the same things, it’s possible, probable or even near-certainty that we’ll get different results each time. Or, conversely, that to get the same effective-result in each case, we might, may or must do things differently each time. Which, for the latter, means that we need to know what to do differently each time. Hence, as Claire Lew put it, in that same Twitterstream:

- cjlew23: If you want your company culture to be a certain way, figure out which behaviors you are enabling – and blocking. @AlexOsterwalder #BoS2015

And just to make it even harder, it’s often very different in practice than it might at first seem in theory – as that skew in the tame/wild diagram above suggests. Which is why this gets kinda tricky…

Which brings us back to the question of whether culture-change is the same as software-change. Because a lot of the answer to that depends as much on how we understand software-change as on how we understand culture.

If we think of software-development as just programming a machine to do the same thing over and over, in a supposedly-’logical’ way, then yeah, we’re likely to approach culture-change in much the same manner, too – viewing the organisation and the people within it as programmable, predictable, controllable elements within a machine. That’s pretty much the Taylorist dream: programmable people, piling up the profit for the ‘owners’ and the managers too.

But the catch is that it does not work with cultures. Cultures are ecosystems: and the outcomes of an ecosystem are always an emergent effect arising not just from the sum of the elements themselves, but from the interactions between the elements of that ecosystem. So even if we could somehow program every one of those people to respond always in the exact same way, the overall outcome would still be somewhat unpredictable, always somewhat ‘out of control’. The only thing that ‘control’ does do well is suppress all creativity, innovation, difference – which, since these are themes that most organisations often need the most, makes a ‘control’-based approach to culture self-defeating even before it starts.

And it not only does not work for cultures, it doesn’t work all that well for software-development either. Hence the Agile Manifesto and its underlying human-oriented principles. If we approach software-development as an expression of human culture – rather than solely an attempt to define how to ‘control’ a machine, in a context that’s broader than just that one machine – then we do it in a very different way. Usually a much more successful way, too.

But what definitely does not work is doing it in a muddled, mixed-up halfway-house. Far too many so-called ‘Agile’ teams try to gain all the advantages of genuinely-agile development – rapid pace, iterative development, higher quality – but whilst still clinging on to a rigid top-down command-and-control culture. It doesn’t work: we end up with the disadvantages of both approaches, and the advantages of neither…

The same with cultural change. There are some parts to which tame-problems do apply, and do work. Yet even regulatory compliance won’t work if the culture doesn’t support it – as in a classic ‘pass-the-grenade‘ culture, for example. Hence, as Dave Gray put it, somewhat later in that Twitterstream:

- davegray: Culture is like a garden. It can be designed or grow wild but either way, it evolves organically @jamesarcher @13bitstring @AlexOsterwalder

And late towards the end of that Twitterstream – or perhaps just coincidentally anyway - Bard Papegaaij dropped in with three comments that are crucially important for culture-change:

- BardPapegaaij: First rule for dealing with complex systems: you are a part of, not apart from, the system you operate in. #Complexity

This is where culture-work will necessarily part company from Taylorism, because the latter is always about ‘doing’ change to others, or at others – rather than what is actually needed here, which is to accept being part of and embedded within the change itself. Yes, in all culture-change, we work with what facts we have: but often feelings are the most important facts that we face here – even though they’re not what most Taylorists would think of as ‘fact’…

(At this point it’s probably worthwhile remembering the old warning that “people do not resist change, they resist being changed” – especially if they perceive the change as being only for the benefit of others, at the expense of themselves.)

All of which is reaffirmed in Bard’s second note:

- BardPapegaaij: Second rule for dealing with complex systems: there’s no ‘outside perspective’ of the complex system you’re part of. #Complexity

This is why a cultural change only works when it’s modelled in action by leaders and others. If the self-styled ‘leaders’ demand that everyone else should change, but change nothing in the way that they themselves do things, in how they relate with others, and so on? – well, no, it ain’t gonna fly. People take note of what leaders do – not just what they say they’re going to do…

(Stafford Beer’s POSIWID is another useful reminder here: “The [effective] purpose of the system is [expressed in] what it does” – not just what people say it ‘should do’.)

And Bard’s third note brings us back to a key difference between tame-problems and wild-problems:

- BardPapegaaij: Third rule for dealing with complex systems: simplification doesn’t improve the system; it usually dramatically degrades it. #Complexity

For tame-problem elements in a context, Taylorist-type tactics probably do apply: simplify, simplify, simplify. But for wild-problem elements, as Bard warns, attempts at simplifying will almost invariably make things worse – not least because overly-simplistic ‘solutions’ so often slice off or elide over crucial nuances upon which success and viability would depend.

Which perhaps brings us to one last point, about anticlients – because the reality we face is that a flat-footed, over-controlling ‘culture-change’ risks creating not just vast numbers of anticlients, but vast numbers of anti-employees too. Perhaps take a look at the post ‘Anticlients are antibodies‘ for more information on that? – it’s not a risk that we could wisely ignore…

Leave it at that for now, anyway – over to you for comments and suchlike, if you wish?