Enterprise-architecture – a status-report

Blog: Tom Graves / Tetradian

For me, the past couple of months or so has been somewhat of a whirl: keynotes and several other presentations at five conferences, a blur of small consultancy-gigs, maybe a dozen workshops, and a whole lot more, across six countries on three continents, and some 30,000 miles of travel. Might be good to slow down for a while and get my thoughts together on this…

The main theme that’s come up during that time has been about how fast the disciplines and scope of enterprise-architecture are changing – or needing to change, rather, whilst most of ‘the trade’ is still adamantly clinging to the misbegotten stasis of the past. Which is kinda sad, really. Anyway, various insights on this from my travels:

– TOGAF as a verb: So dominant is the TOGAF brand within ‘the trade’ that it seems in some countries it’s actually become a verb: ‘to togaf’, or “we will do your togaffing for you” – in much the same sense as the Hoover brand became a verb for vacuum-cleaning (‘hoovering’) or the Xerox brand for photocopying (‘xeroxing’).

That would no doubt seem nice for the Open Group and their licensees, of course. But in reality it’s more than bit unfortunate for all of us, because TOGAF covers only a tiny subset of the literal ‘the architecture of the enterprise’, and is essentially a disparate collection of so-called ‘best-practices’ rather than a proper usable standard, with most of them largely-outdated at that – and hence not usable for most of where EA is going. If TOGAF really is becoming a verb, then sorting out the mess that is current ‘enterprise’-architecture is going to be whole lot harder – and with an increasing risk that it may not be possible to recover it at all.

Which brings us to…

– Most mainstream ‘EA’ frameworks were built by and for ‘big-country’ cultures: Nothing wrong with that as such, of course, yet we need to realise that it does have real consequences. Probably the most important of these – and perhaps especially so in the US – revolve around embedded yet hidden cultural assumptions, and assumptions about scope and scale:

- impact of hyper-individualism and ‘WEIRD’ culture

- impact of hyperspecialism, especially in large organisations

- focus is on large transaction-oriented IT-systems in large to very-large organisations or consortia

In that type of context, architecture itself ends up becoming a kind of specialism in its own right, and probably the only viable way to link everyone and everything together is through formal documents and definitions – a context in which, for example, John Zachman’s bizarre assertion that “engineering an enterprise is the same as engineering an aircraft” can sort-of seem to make sense. A side-effect is that this also drives everything towards hierarchical, top-down, Waterfall, and organisation-centric – because that’s just about the only way that anything can be made to work in that type of culture and context.

Which, in turn, both describes and explains pretty much all of the mainstream ‘EA’ frameworks such as Zachman, DoDAF, FEAF, TEAF and TOGAF – the latter being the only one amongst them that bothers to define any kind of method, and which probably also in part explains its over-dominance in ‘the trade’.

Yet for ‘small-country’ cultures – small nations, or those with a small technical-pool for EA-type work – the underlying assumptions and needs are almost the exact opposite:

- cultures tend towards collaboration or consensus

- shortage of skilled people necessarily mandates generalism and/or ‘serial specialism’

- focus is on end-to-end cross-functional integration in medium to smaller-sized organisations

In that type of culture and context, architecture is more an underlying habit than a specialism as such, and anything too document-heavy is seen as irrelevant overkill – not least because there simply isn’t time to produce, digest and use all of those documents. A side-effect is that this also drives everything towards distributed-authority, bottom-up or sideways-out, Agile, and outcome-centric – because that’s just about the only way that anything can be made to work in that type of culture and context.

Which, in turn, mandates the need for EA-frameworks to match up to those requirements – which those ‘big-country’-oriented ‘EA’ frameworks barely serve at all. Oops…

And ’twas ever thus, no doubt – hence, I suspect, this lovely little handmade item I spotted in the Second World War section of the New Zealand Navy Museum:

Which probably wouldn’t matter all that much, except that…

– Where EA is headed fits ‘small-country’ culture better than ‘big-country’ culture: We’re seeing a huge changes going on right now, all of which demand a different approach to EA and integration:

- increasing use of public-cloud lessens the importance of in-house big-IT, and mandates better understanding of how information fits into the broader business-architecture

- newer interaction-models such as mobile and social mandate a shift from organisation-centric ‘inside-in’ or ‘inside-out’ to a more customer-centric and outcome-centric ‘outside-in’

- in many contexts such as helpdesk call-centres, kanban-systems and some types of manufacturing, humans are increasingly required to take over in the ‘wild-problems‘ where tame-problem automation cannot reach

- increasing complexities in supply-chains and value-webs mandate integration across the whole end-to-end flows, requiring interweaving (rather than separation) of all IT-based, machine-based and human-based elements of flows

- increasing doubts on the economic and/or sociopolitical validity of the still-dominant neoliberal views on economics and business, driving real political unrest in many countries, and pointing towards increasingly-fundamental shifts in legislation, regulation and more

- increasingly, the old Waterfall methods are too slow and cumbersome for the still-accelerating pace of change

- new elements and materials are blurring the old hardwired boundaries between technology, applications and data upon which the mainstream ‘EA’ frameworks depend

And in practice, all of this now applies just as much in the ‘big-countries’ and in the ‘small-countries’. In other words, the mainstream ‘EA’ frameworks that we now have are almost perfectly unsuited for the real EA contexts that we now face. Although some of us have been working hard for some years now to remedy this situation, it’s still an uphill struggle all the way, against the dead weight of those now-dysfunctional frameworks – especially as each ‘success’ of the vested interests in selling those old frameworks actually represents yet another step in the wrong direction, yet another person who’ll have to unlearn just about everything they’ve been taught about ‘EA’ and start again from scratch. To give just one example…

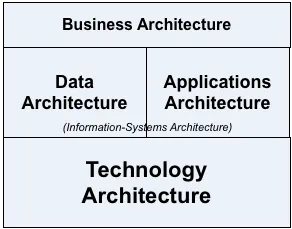

– The BDAT stack is no longer a useful model for most EA: I’ve written about this elsewhere, but the blunt reality is that the so-called ‘BDAT stack’ model – distinct layers for Business, Data, Applications and Technology – has now gone well past its ‘use-by’ date. The BDAT-stack is right at the core of just about all of the mainstream ‘EA’ frameworks, and it did sort-of make sense as long as we were only ever concerned with IT-infrastructure. But the further we moved from that one specific concern, the less useful it became – and to be blunt, it’s not much of a concern for most EAs now. Instead, what is a concern now would include:

- cloud-based shadow-IT and suchlike, in which ‘non-IT’ folk define their own applications and data

- mobile apps that bundle application and data as a single package

- virtualisation and ‘serverless’ computing that blur hardwired relationships between applications and infrastructure

- ‘Internet of Things’ sensors and suchlike, that bundle together technology, data and dynamically-reprogrammable applications as a single package

- ‘intelligent materials’, often derived from nanotechnology, through which physical objects may embed programmable physical/analogue ‘applications’

- wearables, embedded-technologies and human-augmentation that combine any or all of these elements

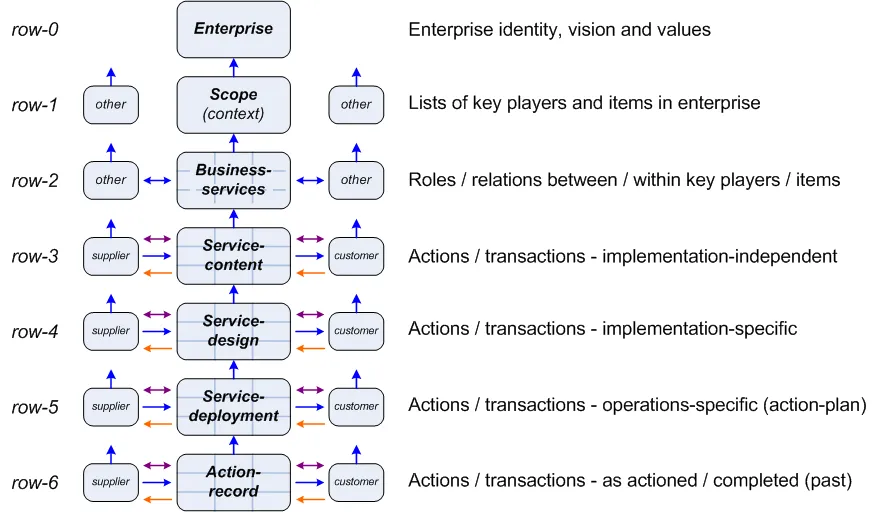

And, on top of that, we have the increasing development and integration of AI, autonomous-robotics and machine-to-machine business-relations, in which the classic boundaries between ‘business’ and ‘technology’ are beginning to blur. Increasingly, then, the only ‘layering’ that makes sense for EA is that of layers-of-abstraction, not layers-of-function – in other words, from this:

To something more like this:

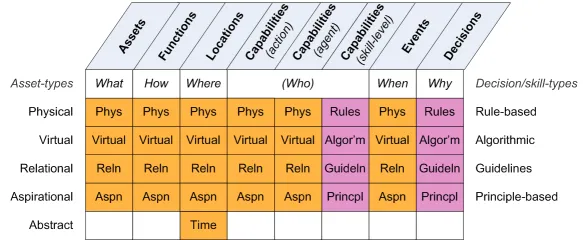

Within which we identify the architectural structure and content not from arbitrary and incomplete set of domains (as in the BDAT-stack), or an arbitrary and incomplete set of hardwired entities (as in Archimate), but from an explicit, consistent, systematic set of of content-attributes such as these:

So, given all of that, and going in the other direction…

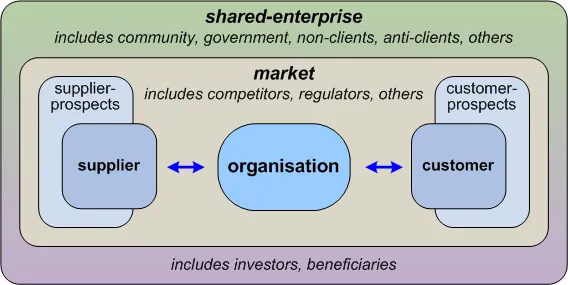

– The next trap to avoid in EA is ‘business-centrism’: IT-centrism is problematic enough, but business-centrism is arguably even worse, and I still see people fall into this trap far too often for comfort. The most common cause of this mistake is in failing to understand that ‘organisation’ and ‘enterprise’ represent concepts that are fundamentally different from each other. If we blur them together, we would be stuck with a meaningless self-centric view of the organisation alone – organisation as ‘the enterprise’:

Versus what we actually need, which is a clear way to place and describe the organisation in context of all of its stakeholders:

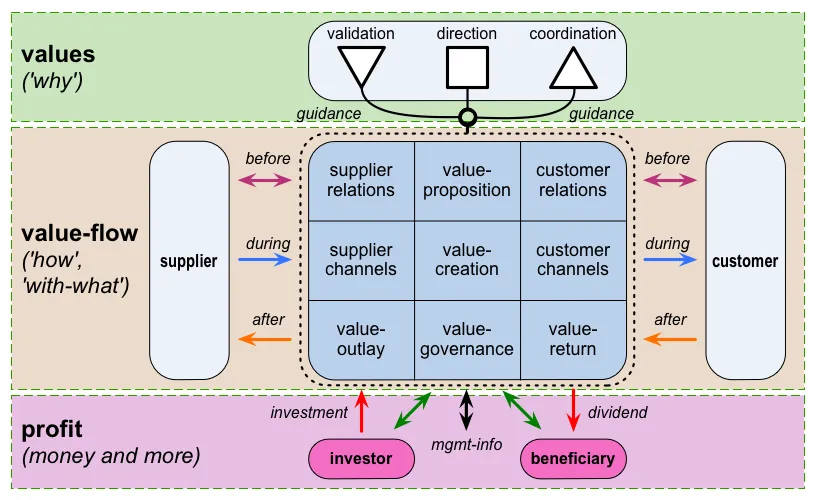

Or, if we describe the organisation in terms of services, the difference between a viable self-adapting service, again in context of all of its stakeholders:

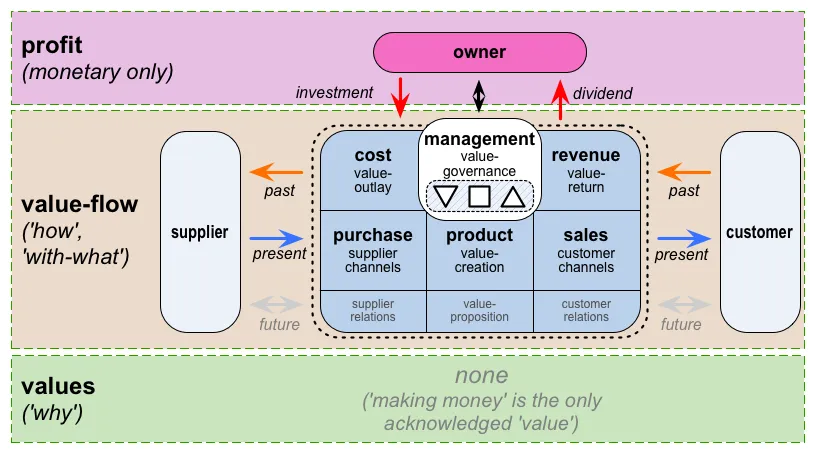

Versus an upside-down, back-to-front, past-focussed, neo-feudal disservice that serves the insatiable demands of one arbitrarily self-selected subset of stakeholders (the ‘owners’) by stealing from everyone else:

It’s a business-architecture mistake, both in terms of structure and story, that over the longer term in particular is literally non-viable for everyone involved. Otherwise known as Not A Good Idea…

The catch is that it’s still a very common mistake, not least because it’s very popular with those who believe that they benefit from its non-viability – otherwise known as the stock-exchanges, the finance-system and all of the other parasites on the real business-economy. For everyone else – as becomes immediately evident once we apply enterprise-architecture principles and practice to the ‘really-big-picture’ scope and scale – it’s an ongoing disaster that is already causing untold harm on a global scope and scale, and may yet kill us all. (Yes, it really is that bad…)

Yet the basis of this whole mess is an arbitrary choice, an arbitrary belief in what is, bluntly, a religion of money. The whole thing is held together by little more than wishful thinking, greed, myopia, short-termism, an over-dependence on shallow and simplistic thinking, and a vast amount of circular-reasoning and ‘policy-based evidence’. If we wanted to – and, more to the point, if we want a better world than the one we’re headed towards right now – then we can choose otherwise: and there are far better options than this current mess. The only thing that’s stopping us do so is the inertia of habit and unassessed assumptions – something about which enterprise-architects should always be wary.

Quite often during my travels I came across business-architects and others who were still building business-models and more, that assumed that money was the only form of value that mattered in an architecture, or that maximising ‘shareholder-value’ – increasingly derided by economists as ‘The world’s dumbest idea‘ – should be the only aim. Business executives will no doubt cling on to such mistakes for a long time yet, because they make their own tasks seem so much simpler: but architects should not fall into that kind of simplistic trap, and instead build their architectural assessments around the whole shared-enterprise, rather than only the illusory ‘easy bits’.

Staying at the big-picture level for a little while longer…

– An urgent need for a fundamental rethink of jobs and work: Courtesy of TOGAF and its ilk, most enterprise-architecture is still overly-focussed on IT and computer-based technologies in general, with little attention paid to the impact of those technologies in the wider world. Throughout many discussions and more during my travels, it became increasingly clear that there are many broader-impact challenges on these themes that are well within scope for ‘the architecture of the enterprise’ that are barely being addressed at all as yet – and urgently need to be. These include:

- economic fragility from shortages of skilled people and lack of provision of skills-education – there seems to be a lack of awareness of how long it takes develop the requisite skills for AI and the like

- economic fragility due to lack of ability to understand or manage financial AI-systems – early versions of which were directly implicated in both the 1989 and 2007-8 financial crashes

- socioeconomic fragility and sociopolitical disruption due to AI/robot ‘takeover’ of many existing jobs – benefitting the ‘owners’ but disrupting the livelihoods of whole regions

(There are also a real concerns about economic fragility from over-reliance on computer-based technologies – “we moved the entire global economy onto the internet without a backup plan”, leaving us wide-open to risks such as a Carrington Event solar-storm or a catastrophic space-junk debris-cascade, or known-unknowns such as a geomagnetic reversal. But that’s probably another story for another time…)

Without appropriate balance on these themes, the vaunted ‘AI/robot future’ risks fizzling out for lack of skills to build or maintain it; burning out in destructive fashion from failure to prepare for unintended consequences; or triggering an all-too-understandable Luddite-style reaction that, if left unchecked, could bring down the entire socioeconomic structure worldwide.

As I understand it at present, probably the only way that this is going to work out well is if we rethink from scratch the concept of ‘a job’. In its current form, a ‘job’ is actually a conflation of two fundamentally distinct socioeconomic concerns: access to societal resources (‘making a living’) and meaningful work (‘making a life’). Under the neofeudal assumptions that have underpinned most economists’ concepts of work for the past few centuries, socioeconomic-class still largely determines one’s ‘rights’ to either of these: for many, especially in the so-called ‘working-class’, it’s not just a trade-off between ‘making a living’ versus ‘making a life’, but all too often barely making either of them at all – and that’s only going to get worse as the ‘AI/robot future’ starts to hit home. Concepts such as ‘guaranteed minimum income for all’ may help to resolve some of the challenges here, which would also enable a stronger refocus on meaningful-work and ‘making a life’ – but we need to be aware of the backlash against such ideas, not just from the economic-parasites but also from societal deep-stories such as the more dysfunctional or blame-based forms of the ‘Protestant work-ethic‘. The disciplines of enterprise-architecture could help a great deal in these explorations – and I’d suggest that it’s more than about time that more of us engaged in our responsibilities there.

Which brings us to one last point…

– An urgent need for better tooling for enterprise-architecture: We can only do the work well if we have the right tools to do that work – which, in terms of toolsets for enterprise-architecture, for the most part don’t exist. I’ve written extensively about this theme on this blog, of course, but in the past few months it’s been really hammered home to me again – such as in the discussions on toolsets that I’d had during the recent Gartner EA conference in London. The quick summary is that almost all existing ‘EA’ toolsets are not only tightly locked to the mainstream ‘EA’ frameworks, but they also focus almost exclusively on support for final solution-design, and provide almost no support for the really hard part of EA work, at the front-end of ‘the Squiggle‘. Which, bluntly, often makes them not just doubly-useless, but worse than useless – in some cases trying to force us to do the work in exactly the ways that it should not be done. We really, really need to do a better job on this… – and whilst that fact is slowly, slowly beginning to sink in, it’s still more amongst small independents rather than the big toolset vendors. Oh well.

Best stop there for now, I’d guess: over to you for comments, perhaps?